GIS decision maps form roots for conservationists’ long view for community resilience

By Ben Young Landis

Atlanta, Georgia, is no stranger to the concept of resilience. The greater metropolitan Atlanta is among the ten largest cities in the United States, and has been the site of some of this country’s most significant battles over human dignity.

For The Nature Conservancy — a U.S. nonprofit organization — greater Atlanta is not simply another project site, but a community that demands exceptional respect and care. Atlanta is one of 21 cities in the Conservancy’s North America Cities program, which seeks to assist residents in leveraging local natural infrastructure — such as forests and coastlines — to reduce pollution and enhance resilience and urban biodiversity.

In any given slice of Atlanta’s skyline, forests and greenbelts are a visible presence in both the foreground and stretching into the horizon. (Image courtesy of NASA DEVELOP)

In Atlanta, the Conservancy sees the region’s existing, astounding proportion of urban forests — cited as the highest among major U.S. cities — as a central asset. Protecting and restoring the city’s forests would be an investment in community resiliency for the city. But early feedback from stakeholders indicated that any forest management strategy must be strongly tied to water quality benefits. Urban runoff pollution is a sensitive regional issue, as Atlanta’s upstream seat on the Chattahoochee River garners it much criticism for any downstream impacts in water supply and shellfish health.

The Conservancy’s first need, it seemed, was to create a literal roadmap of urban forest corridors with the highest potential for runoff control and long-term conservation benefits for Atlanta. The map would be a centerpiece for community-driven conversations and decisions between local leaders, agencies, and the Conservancy in charting a vision for Atlanta’s precious environmental assets.

A Community of Future Research Collaborators

Fortunately for The Nature Conservancy, a NASA DEVELOP team with specialists in mapping analysis worked just over an hour away, at the University of Georgia.

Advised by University of Georgia professors Marguerite Madden, Rosanna Rivero, and Adam Milewski, the team in Athens, Georgia, is one of 12 “nodes” around the country managed by NASA DEVELOP. Each node fields rotating teams of undergraduate and graduate students and early-career and transitioning-career researchers who gain training in technologies and methods in the earth sciences while working on projects for real-world clients. The applications and tools these DEVELOP participants create have a chance to directly help client organizations and communities solve timely natural resources issues.

“The students work with NASA, so it’s an amazing part of their portfolio,” says Madden, who is Director for the Center for Geospatial Research at University of Georgia. “It offers professional development as well as academic training.”

Sean Cameron, who recently completed his master’s degree at the university, was appointed project lead for the Conservancy’s Atlanta mapping effort.

“Urban forests offer unique opportunities for stormwater management,” says Cameron. “Forests help filter stormwater before it reaches major channels. And as demand for clean water grows in Atlanta — our population is projected to add another 2 to 3 million people in coming decades — that adds demand on the municipal water infrastructure.”

Cameron appreciated the Conservancy’s challenge to promote forested lands protection and reforestation as a path to urban conservation and community well-being. Working with other DEVELOP participants with the node’s lead, Caren Remillard, Cameron set out to create a “decision support map” that the Conservancy needed to identify priority conservation areas within greater Atlanta.

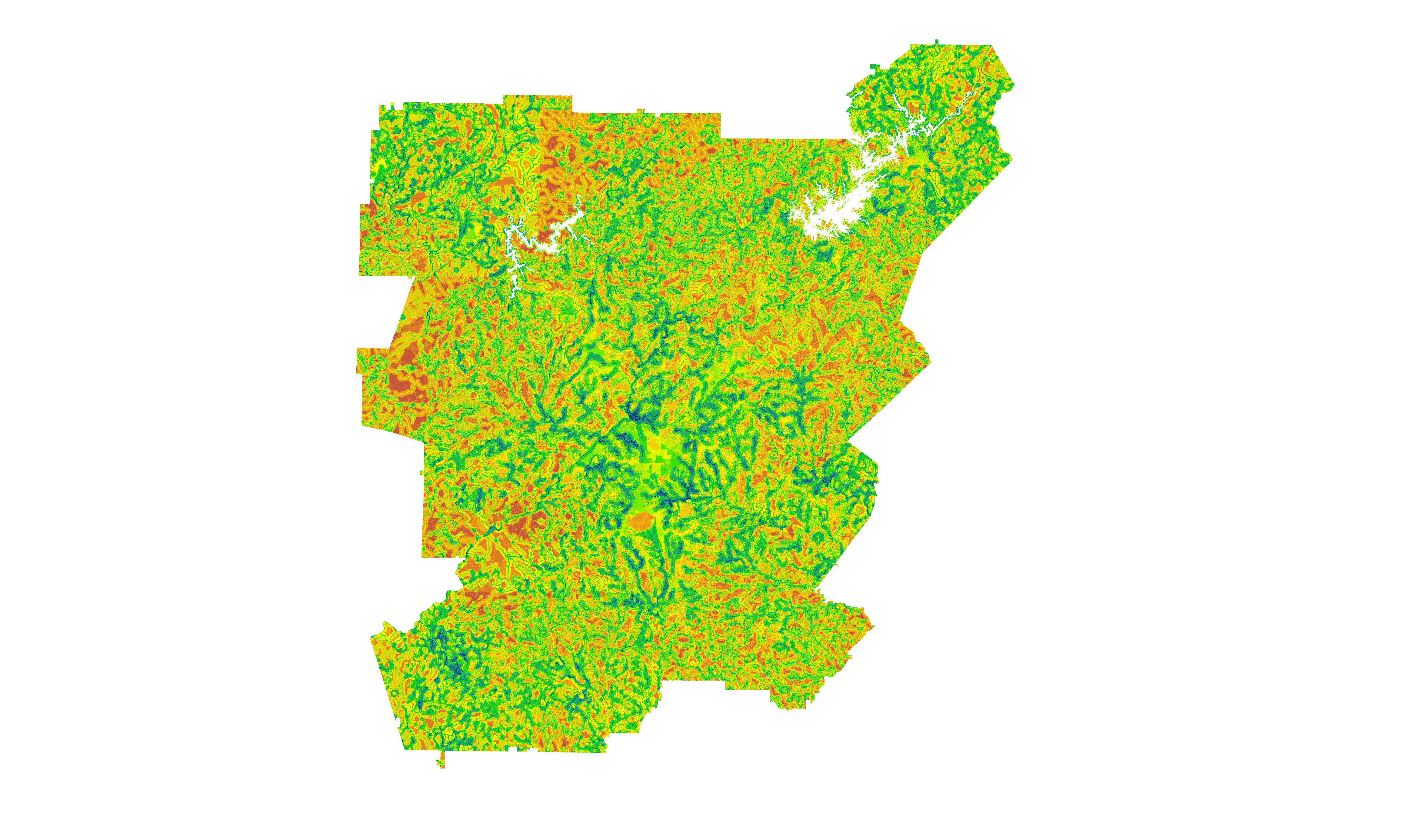

The kaleidoscope of colors in the GIS decision map created by NASA DEVELOP’s University of Georgia team will help The Nature Conservancy chart a future for urban forestry and water quality management in greater Atlanta. (Image courtesy of NASA DEVELOP)

“Under this land-use-conflict identification strategy, there were three water management goals we wanted to optimize for across Atlanta,” explains Cameron. “We wanted to find areas where existing forest cover could minimize untreated stormwater flow from nearby sources, such as roadways; areas with existing greenspaces primed for conservation management; and areas with additional potential to protect local water quality.”

Using geographic information system (GIS) tools, Cameron and colleagues analyzed greater Atlanta’s land cover characteristics via NASA satellite data, and assigned scores to areas where vegetation and topographic features satisfied one, two, or all three resource management goals.

The resulting land-use prioritization map ranks areas across the 15-county landscape in order of their conservation potential for urban forestry and water quality. “The highest priority areas are ones that maximize all three goals,” says Cameron.

“The map facilitates decision making,” says Rivero, of the College of Environment + Design at University of Georgia. “Everyone in the community can use this map, looking down to the watershed and across the whole region.”

Collaborative Research for a Community’s Future

“Working with this group of students and professionals quickly became a very positive experience that yielded useful products and a great partnership between our organizations,” says Sara Gottlieb, conservation planner for The Nature Conservancy in Georgia.

In addition to creating the decision support map, Cameron and other participants also engaged in stakeholder meetings in Atlanta — presenting their findings to municipal managers — and even in volunteer tree-planting days with a local non-profit, Tree Atlanta. “We try hard to keep our participants involved in the local landscape,” says Remillard, the DEVELOP node leader.

Myriam Dormer, the outreach and urban conservation associate with the Conservancy in Georgia, knows all about the value of getting involved in the local landscape — and putting in the groundwork to build relationships and understanding with the people who live there.

“It’s much more complex than just coming to a community and saying, ‘Trees are good, and we need trees,’” says Dormer, who is based in Atlanta. “We want to understand what the community is experiencing in terms of challenges, listening to see where we as an organization need to come in.”

The NASA DEVELOP decision support maps are merely the early roots of The Nature Conservancy’s long-term vision for community-driven conservation, with real action on the ground, including tree plantings and stakeholder town halls. (Image courtesy of NASA DEVELOP)

Dormer explains that for the Conservancy, the decision map is just step one in the long-term strategy of securing Atlanta’s resilience through natural infrastructure. A second stage, now under way, will work with community-based organizations to examine the socioeconomic conditions in neighborhoods bordering priority forest conservation areas.

Early meetings with community stakeholders revealed important concerns — implications for affordable housing, for one. While greenspace preservation is important, overall demand for urban development in Atlanta is raising local property values. Forest conservation measures may inadvertently price out the very communities the Conservancy hopes to serve, if safeguards are not considered in tandem.

The Conservancy is also taking care to understand community voice and capacity. “We don’t want to extinguish the community’s self-healing response,” says Dormer. “The people must be part of the process.” Rather than simply setting conservation goals for Atlanta’s communities, she emphasizes that a key part of the Conservancy’s process is to hear what those communities want, what their concerns are, and what role they’re willing to play.

It’s a process that starts with a good map, of course. And while the goal may be to chart urban land use options for Atlanta, the Conservancy values the conversation itself as an achievement in building resilience.

“A lot of times, we’re so focused on the end goal that we don’t take the careful approach to create the right type of engagement with our communities,” says Dormer. “It’s important for these communities to see that they have a place in these conversations. The process is part of the goal.”

Ben Young Landis is a contributing writer for Creative Science Writing and the Thriving Earth Exchange.

More Resources

Watch the Atlanta Water Resources project video created by the NASA DEVELOP University of Georgia team: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cRJTKr271aE

Read another AGU Thriving Earth Exchange story about NASA DEVELOP collaboration in natural resource planning: https://thrivingearthexchange.org/tex-stories/art-helps-scientific-collaboration-come-life/