Communication and relationship building between scientists and community proves key to successful study

By Nancy D. Lamontagne

In the past few decades, the area around the small, rural town of Pavillion in north central Wyoming has seen substantial growth in the number of wells used to extract natural gas from the region’s tight gas sands. Many of the 169 active vertical gas production wells and much of the associated gas infrastructure are located very close to the houses and farmland where local residents live and work.

John Fenton, a farmer in Pavillion, points out farms and gas development sites. Photo courtesy of Coming Clean.

“We are always smelling emissions from the equipment and the tanks,” said John Fenton, a farmer in Pavillion. “We have to close our windows during the summer, when you want to let the nice air in, because the smells are so bad. We also had strange health problems that the medical community had been unable to explain.”

Pavillion is a rural town of just 240 people with around 200 more people living on family farms east of the town. After studies revealed contaminants from gas production in the water and high levels of toxic chemicals in the air, community members wanted more information.

“We wanted to know if the chemicals found in the air were also in our bodies,” said Fenton. “That took us down this road of cooperatively working with scientists to see if we could find out what we were being exposed to and what was in our bodies.”

Building relationships

Coming Clean, an environmental health and justice campaigning collaborative, coordinated a new study to examine whether chemicals found in the air emissions from gas production equipment were also detectable in Pavillion-area residents. Partners in the study included the non-profit organizations Clean Production Action, Commonweal, Pavillion Area Concerned Citizens, and ShaleTest. Deb Thomas, director of ShaleTest, identified a team of scientists from the University of California, San Francisco and Emory University to work with biochemist Wilma Subra of Subra Company on the project.

“What came together to make this project work is what is missing from many interactions: a basic understanding of each other,” said Fenton. “Although we had a short schedule, we took time to build the relationships that led to a successful project.”

Fenton pointed out that the scientists didn’t just listen to the experiences of residents but also visited sites to see firsthand how the gas wells impact everyday life. “It’s one thing to say ‘I have a 400-barrel production tank 220 feet from my house,’ but it is a whole other thing to stand there and to actually smell that, and to experience what the people who live here do every day,” said Fenton.

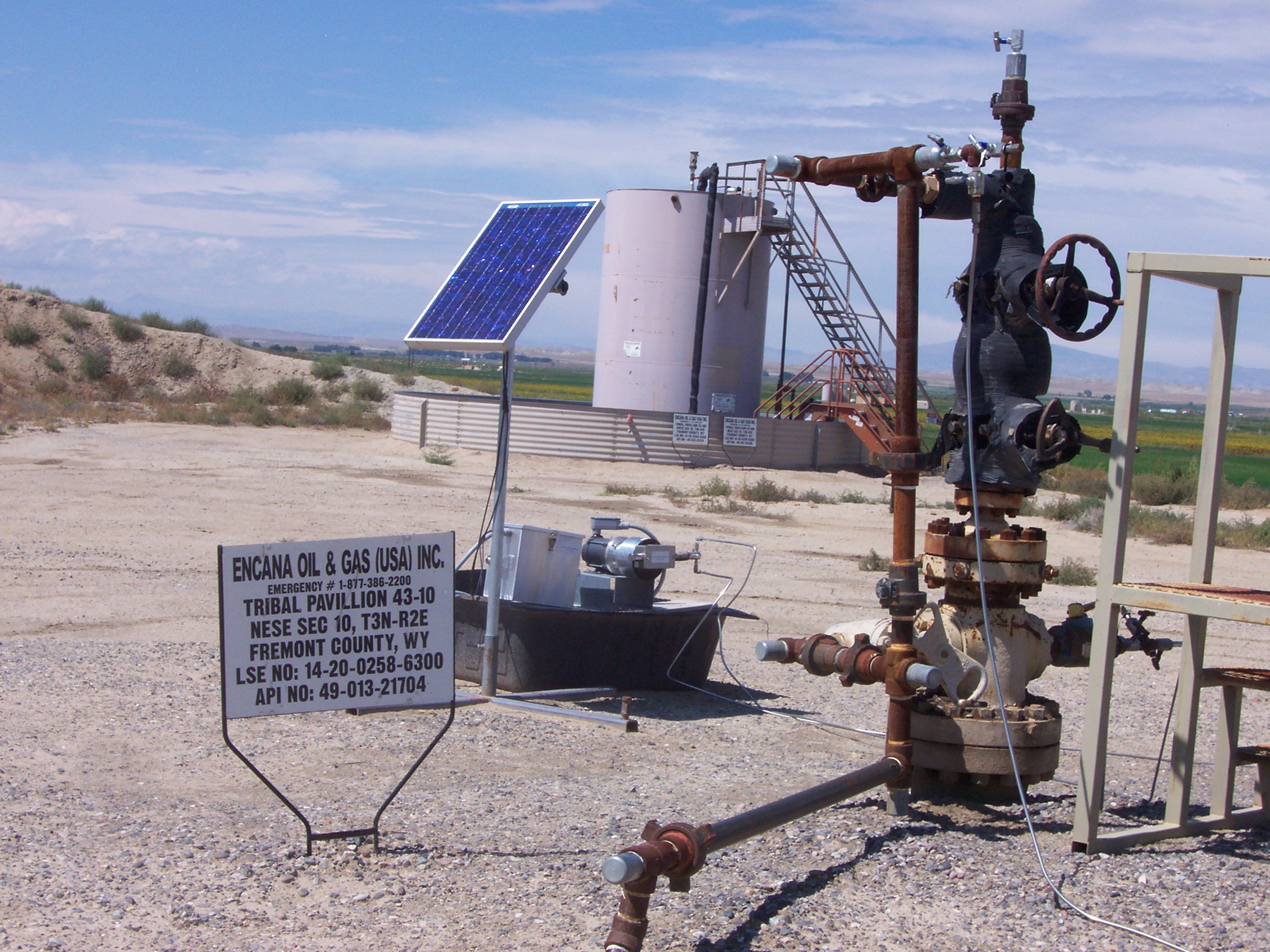

Residents of Pavillion live and work in close proximity to gas extraction equipment such as this. Photo courtesy of Coming Clean.

The people in Pavillion had already gotten a lot of information about potential water and air pollution from previous studies. What made this new collaboration particularly useful was having the opportunity to broaden their knowledge by having people on hand who could answer their questions. “The scientists took us into their community and explained things in ways we could understand about what the testing was, and how it was done, and what we could expect to get out of it,” Fenton said.

Finding answers—but no magic bullet

The project team developed a unique study approach that combined air monitoring, biomonitoring, and hazard assessment to create a picture of what residents are breathing and what health affects might come from these chemical exposures.

Data from the study showed that eight chemicals emitted from gas infrastructure in the area were also in urine samples from study participants. These chemicals have been linked to chronic diseases such as cancer, reproductive problems, and developmental disorders, as well as to problems such as headaches, nosebleeds, skin rashes, and depression. The results were published in the report, “When the Wind Blows: Tracking Toxic Chemicals in Gas Fields and Impacted Communities.”

The report concludes that more needs to be done to protect local residents from harmful exposures, and recommends specific monitoring activities and preventive approaches to help ensure residents’ health and well-being.

But while the study has armed Pavillion residents with knowledge to present to government and industry, it doesn’t guarantee that residents will be better protected. “All this information is very good and helps people understand what is in their bodies, but this won’t be the magic bullet that solves all the problems,” said Fenton.

Fenton said that an important outcome of this latest study is that other groups have expressed interest in using some of the study approaches and techniques used in Pavillion to examine oil and gas pollution at other locations. “It’s one thing to show the impacts of gas production in Pavillion, but if we can replicate this work in other places that have similar impacts, then it will be hard to ignore the problem,” he said. “These studies are very important because more and more people are living close to oil and gas operations.”

Nancy D. Lamontagne is a freelance science communicator and a contributing writer for Creative Science Writing and the Thriving Earth Exchange.

Read more: