American doctoral student collaborates with government health researchers to better understand water treatment methods in rural China, leading to formal research collaboration between U.S. university and Chinese agency

By Nancy D. Lamontagne

Most people living in rural China treat their water via boiling, a practice that can produce harmful indoor air pollution. Photo courtesy of Alasdair Cohen.

Around the world, 1.8 billion people lack access to safe drinking water. Many must collect their own water and treat it in the home to remove dangerous bacteria and viruses. One common method of home water treatment is boiling, which is typically done by burning fuels like wood and coal and thus contributes to air pollution problems.

Though the majority of the more than 600 million people living in rural China have access to piped water, many treat their water by boiling. Alasdair Cohen, now a postdoctoral scholar and environmental health scientist at the University of California (UC) in Berkeley, recently completed one of the first studies of household water treatment in China as a doctoral student in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management at UC Berkeley.

Cohen’s research project required a great deal of patience and perseverance as he formed partnerships with government agencies in China, developed a study approach that considered the sensitivity of issues related to drinking water quality, and communicated research methods to government workers in China. This hard work not only produced information that could help more people get access to safe water in rural China—it also led to a formal collaboration between UC Berkeley and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) to work on joint initiatives related to water, health and the environment.

Making the right connections

Cohen became interested in studying the methods used for household water treatment in rural China while choosing a topic for his doctoral research. This interest partially stemmed from his previous work on United Nations projects in China, including work to develop indicators and metrics to understand water issues and rural poverty.

To get advice on launching this type of research project, Cohen contacted a former United Nations colleague who put him in touch with Zhenbo Yang, the Chief Water and Sanitation Officer at UNICEF in China. Yang then introduced Cohen to Yong Tao, Director of China’s National Center for Rural Water Supply Technical Guidance at the CCDC.

“We knew we would need government approval and coordination to conduct this type of work and to have access to field sites and support,” said Cohen. “It was on the merit of Yang Zhenbo’s decades-long relationship with the director that he agreed to meet with me and listen to my research proposal. It was a very nice surprise that Director Tao was not only interested and supportive, but wanted staff from his agency to be directly involved in the study.”

Cohen’s initial study led to conferences in both Beijing and California that were co-hosted by UC Berkeley and CCDC. Earlier this year, a formal partnership was established between UC Berkeley and CCDC to collaborate on applied research projects and initiatives related to water, health and the environment. Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley.

With the CCDC on board with the project, Cohen and his Berkeley colleagues worked with the agency for the next year to plan the project while gradually building a sense of partnership and collaboration.

“One thing I learned the hard way was to be careful with assumptions,” said Cohen. “For example, we didn’t realize that while our counterparts at CCDC headquarters in Beijing were quite familiar with doing research, their colleagues in the provinces and counties were more accustomed to collecting data for monitoring purposes, so we needed more time to ensure that they understand the rationale for some of our research methods.”

To select households from which to collect survey data and water samples, the researchers invited village leaders to publically draw household numbers out of a basket or hat. This approach worked well, and almost all the randomly selected households were willing to speak with the data collectors and provide water samples. “When the data collectors arrived at a given household, people there had often already heard that the CCDC was visiting the village,” said Cohen. “They also understood that they had been picked by the village leader randomly, like a ‘lottery,’ and not because of something related their household in particular.”

Translating research to policy

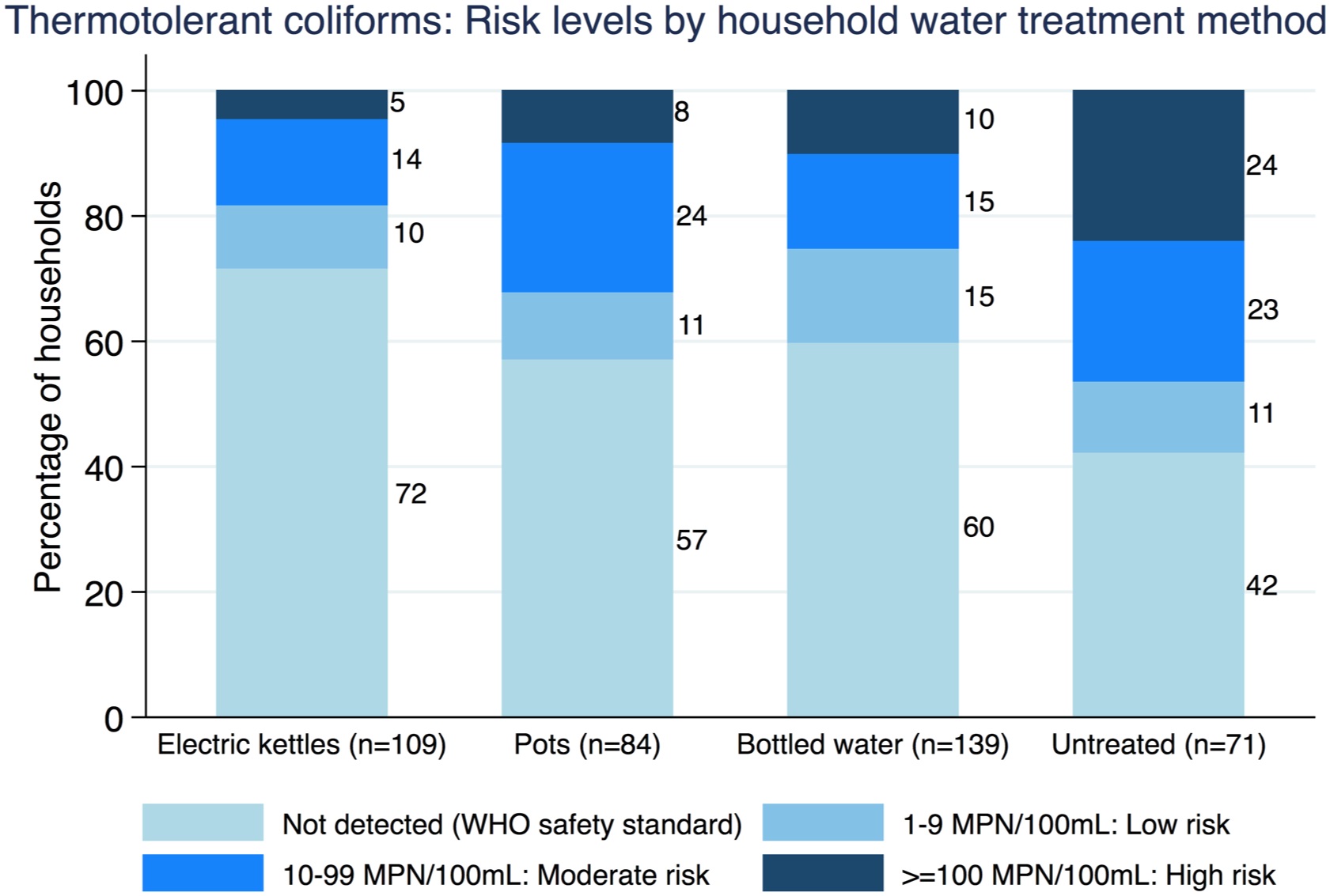

Electric kettle users had the lowest risk of having coliform bacteria detected in their drinking water. Graph from Cohen et al., PLOS ONE, 2015.

Cohen and his colleagues’ study revealed that drinking water from households using electric kettles for boiling showed significantly better microbiological water quality than households boiling in pots, using bottled water or not treating their water. In addition to producing safer water, the kettles also reduce the overall air pollution in the household, require less time to boil water and come with a built-in lid that prevents recontamination after boiling. Compared to boiling with pots over a fire, these are all great potential benefits.

The researchers are now planning an impact evaluation study that will take a closer look at these and other potential benefits by promoting electric kettles, potentially at a subsidized price, to households in poor, remote, rural areas of China. The researchers will examine how using electric kettles impacts drinking water quality, household air pollution, health and the amount of time and energy spent treating water compared to another group of households that will receive no electric kettle promotion.

“There is a lot of great research that gets conducted without a readily available channel from research to policy,” said Cohen. “In this case we’re fortunate that if we find that the electric kettles are clearly beneficial, our CCDC colleagues and other government agencies are in a position to implement a program that promotes their use.”

Cohen and his team are trying to secure funding to continue to work with the CCDC on this and other innovative projects related to drinking water and public health. “We’re working together to try and address a number of pressing environmental health issues in rural China, but have found it difficult so far to secure research funding from traditional federal sources here in the U.S.,” said Cohen. “So we’ve started to look for alternative sources of support such as foundations and other donors.”

Read more:

• Berkeley/China-CDC Program for Water and Health

• New research in rural China may help improve drinking water quality and reduce air pollution

• Cohen A, Tao Y, Luo Q, Zhong G, Romm J, Colford JM Jr, and Ray I (2015) Microbiological Evaluation of Household Drinking Water Treatment in Rural China Shows Benefits of Electric Kettles: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 10(9): e0138451. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138451.

Nancy D. Lamontagne is a contributing writer for Creative Science Writing and the Thriving Earth Exchange.