Fostering climate resiliency on Native American reservations

By Kathleen Pierce

Leanne Hale of the Fallon-Shoshone Tribe stands in a fallowed field. Her tribe received only 20 percent of its water allocation in 2015.

Many people are familiar with the extreme water shortage in the Western United States, but less well-known is the distinctly different water crisis Native American farmers and ranchers in the same area are facing. On reservations, climate change is manifesting as extreme droughts, declining groundwater supplies, and warmer temperatures, compounding long-standing struggles involving land tenure, water access, and geographic remoteness.

Native Waters on Arid Lands, launched in 2015, is a remarkable collaboration among tribes stretching across the Great Basin and the American Southwest, the University of Nevada, University of Arizona, Utah State, Ohio University, Desert Research Institute, First Americans Land-grant Collaboration, and the United States Geological Survey. Its goal is to address water availability, both now and in the future, and promote agricultural resiliency in Native American communities.

Water rights, but little water

“In the arid West,” said Loretta Singletary, Ph.D., an economist, professor, and extension specialist at the University of Nevada, Reno, “if you don’t have water attached to the land, you can’t survive.”

The land tenure situation on Native American reservations is akin to the difference between renting and owning a house, Singletary said. When you own a house, it is yours to alter as you like, or sell again if you need to. On reservations, the land is held in trust by the U.S. government. These circumstances, combined with a chronic lack of operating capital, restricts tribes from fully utilizing their resource assets and limits their ability to move to better land with more water access. “It’s pretty obvious that climate change poses real threats to these communities,” said Singletary.

Further complicating matters is the reservations’ lack of access to what little water there is. While Native American communities have the area’s oldest water rights, many don’t have actual access to the water because the federal government has not invested in water infrastructure like canals, reservoirs, and dams on reservation lands.

Buoys sit in the dry riverbed of the Truckee River in this photo from June 2015. The river exits Lake Tahoe at Tahoe City dam, but because the lake’s water level was below the rim, the Truckee slowed to a mere trickle.

“The combination of the different type of land ownership and the lack of access to water infrastructure has made the tribes in the American Southwest particularly vulnerable to climate change,” said Maureen McCarthy, Ph.D., University of Nevada, Reno’s Tahoe and Great Basic Research Director. “They aren’t able to access the water rights that they have.”

Tapping resources on and off the reservation

Native Waters on Arid Lands is a multi-state, multi-institution, multi-disciplinary collaboration among tribal leaders, tribal extension experts, economists, ecologists, environmental policy experts, climatologists, and hydrologists.

Several team members are scientists and tribal members. Karletta Chief, Ph.D., assistant professor and extension specialist at the University of Arizona’s Department of Soil, Water, and Environmental Science, is a hydrologist and Diné (member of the Navajo Nation) with extensive experience advising tribes on how to apply traditional knowledge to inform climate adaptation. “I’m very committed to working with tribes, and I would like to see them strengthen the ways they address climate change and still maintain their livelihoods,” said Chief.

By combining each contributor’s specialized skills, the team has formed an engaged, trusted partnership that draws on an enormous well of knowledge to improve the community’s resiliency to climate change.

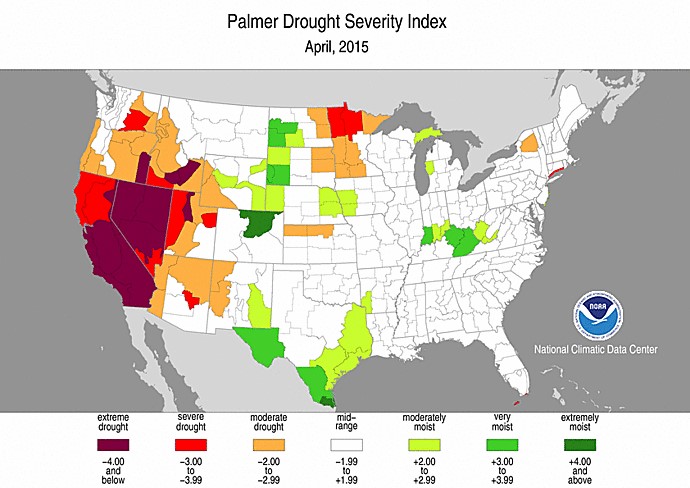

Map showing the severity of drought in the Great Basin and American Southwest as of April, 2015. Image courtesy of NOAA.

Building resiliency

“Community resiliency” is not one simple thing. For a community to be resilient in the face of a changing climate, many elements have to be in place: knowledge of the climate; an understanding of how it might change; access to diverse sources of information; and financial, social, and ecological capital.

Native American communities can be viewed as both vulnerable and resilient. Because of their general lack of financial capital, remote locations, and past exploitations, Native American reservations are highly vulnerable to climate change. However, their history in the United States demonstrates an impressive level of cultural persistence and community resilience.

The Native Waters on Arid Lands team intends to blend this inherent resilience with modern, science-based options for responding to inevitable climate change. The project’s three main goals are to conduct research, share knowledge, and evaluate solutions to improve the tribes’ ability to adapt to and thrive within the complex agricultural, ecological, and economic impacts of climate change. A yearly Tribal Waters Summit further fosters discussion, creates a space for stakeholders to share knowledge, and engages disparate communities.

The team has begun collecting knowledge from several different sources, with an emphasis on traditional tribal agricultural, ecological, and hydrological knowledge that has been passed down over the generations. Researchers will also use modern computational and analytical tools to determine current water availability on tribal lands, model future water availability based on different climate scenarios, analyze water rights policies, and consider the costs and benefits of using various water management tools. “We want to really understand what issues are preventing tribes from fully accessing and managing their water resources to support community resiliency,” said Singletary.

Once the research has been gathered, it will be shared with the communities. At the annual Tribal Summit and at smaller, local meetings, residents and researchers can better comprehend what water resources exist and how they could be affected by various climate scenarios. That knowledge will be made available in an information portal for a wider audience.

Native Waters on Arid Lands project area map, showing reservations in Nevada, Oregon, Idaho, Utah, Arizona, California, Colorado, and New Mexico. Illustration courtesy of Ron G. Oden for the University of Nevada, Reno.

From knowledge to decisions

The final stage of the project will be to evaluate options for each tribe to successfully adapt to potential climate scenarios. Researchers and community members will work together to model and evaluate existing water infrastructure, potential improvements, and agricultural practices. With this tailored information, communities will then be able to make informed decisions for thriving amid a changing climate.

“It’s a different way to think about how we create scientific knowledge,” said Derek Kauneckis, Ph.D., an environmental policy expert and associate professor at Ohio University’s Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs. “It’s about how we get that science to those who need it to better their own communities.”

Staci Emm, Mineral County Extension Educator, has spent her life on the Walker River Reservation in Nevada. “A lot of the climate issues that we’re dealing with, I live them personally,” she said. “In the West, water is becoming more and more valuable. I want to make sure that what we’re doing will make a difference for these tribes, and that they will be able to plan for their future.”

The project team is also energized by the potential for the specialized knowledge they’re generating to be useful to a wider audience. Collecting traditional knowledge and blending it with modern climate science can be done in any community around the world, helping to address the common threat we all face: climate change.

Additional resources:

Kathleen Pierce is a contributing writer for Creative Science Writing and the Thriving Earth Exchange.