NASA and the Navajo Nation team up to visualize drought

By Ben Young Landis

It’s a challenge to capture the stunning iron-reds, sun-singed greens, and rainbow grays of the Navajo Nation landscape on paper. But the deft, dancing strokes of Vickie Ly and Evan Walbridge’s watercolor brushes come close in a pair of YouTube videos — all while painting an elegant explanation of remote sensing, precipitation modeling, and geospatial analysis.

The illustrated, time-lapsed animations produced by Ly — an earth science researcher and science communicator based at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California — are narrated by the cast of collaborators behind the Drought Severity Assessment Tool (DSAT), a new software that aims to help the Navajo Nation track and manage drought. These collaborators include Theresa Showa and Robert Kirk with the Water Management Branch of the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources, and Cheryl Cary, Michael Gao, Vickie Ly, and others with the NASA DEVELOP National Program, a multidisciplinary effort that uses Earth observations to help address community concerns around the globe.

“This project has taken so many of us. There’s a team here at Ames, there’s a team at the Navajo Nation, and there’s a team back East — all the different roles and players who have put in the work,” says Ly. “And we’ve developed a friendship. We’ve developed a family of thought.”

Once it has been refined, DSAT will itself be used to paint a picture of drought conditions for Navajo Nation decision makers — swatches of drought intensity mapped over a sovereign domain the size of Ireland.

Scarcity

Most everyone has seen a glimpse of the Navajo Nation, probably without knowing it. Monument Valley — the unmistakable horizon of buttes, mesas, and spires standing guard near the Utah-Arizona border, made world-famous by countless films and posters — is on Navajo land.

This is but a small portion of the Nation, which stretches 280 miles across (450 km) and overlaps the borders of Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona. Understandably, recording data from stream gages, climate stations and rain collection cans stationed throughout this immense territory has always been a logistically difficult task for the Nation’s resource managers. Currently, managers depend on a network of just 88 rain collection cans to track precipitation levels across 27,000 square miles.

“If you leave the Fort Defiance, Window Rock area, you have to drive all the way, four to five hours to some of these sites — and [water managers] do that every month,” explains principal hydrologist Theresa Showa in one video. “We would like to cut back to where we could manage a few of the sites, and possibly some could be managed by remote sensing. If we could get some of our data remotely and religiously, it would help our program tremendously.”

Precipitation data is of utmost importance because of the ongoing drought affecting the American West, a drying trend that has hit the arid ecology of the Navajo Nation especially hard.

“You can look at [the drought impact] from multiple lenses,” says fellow hydrologist Carl McClellan with the Water Management Branch. “You can look at it from the groundwater or drinking water perspective. You can look at it from the perspective of water availability for agriculture or livestock — there are a lot of Navajo people who utilize the land for farming and their livestock — a lot of people raise sheep or horses, and the availability water is very important. And you can look at it from a fish and wildlife management perspective, with lake levels and such.”

And that’s not even accounting for long-term water scarcity projects due to climate warming and increases in community water demand — or the fact that up to 30 percent of the Navajo Nation’s 180,000 people rely on natural springs, livestock wells, and other off-grid sources for water supply.

Agency

When the Nation allocates internal and U.S. government funds for drought management, it has tended to spread the money evenly across its five agencies and 100-plus chapters — “agencies” and “chapters” being the parallel of states and counties in the Nation’s administrative glossary.

However, the diversity of elevations, habitats, and population densities across the Navajo Nation means that different chapters experience water scarcity differently, McClellan says. “So our need is a tool to explain to the political leaders that while yes, it may seem fair to distribute the dollars evenly, you could distribute drought funding on a need basis, to where the need is greatest.”

The most recognized metric around the world for assessing drought severity within an area is the SPI, Standardized Precipitation Index. SPIs are calculated by taking an area’s precipitation data for a recent time frame — going back one month, three months, or six months in most analyses — and computing its statistical deviation from long-term, multi-decade data averages for that same area.

SPIs are best calculated from a weather monitoring program that has had a long record of reliable data, collected from weather stations evenly and abundantly distributed throughout a study area. In the absence of such data, SPIs can be approximated using precipitation figures from other comparable areas.

The Navajo Nation has two strikes against their SPI values: the challenges of water monitoring in this vast, rural region has made historical field data somewhat unreliable, while nationally available figures for the region are not fine-scaled enough for any meaningful drought planning.

The challenges of water monitoring seemed like a good niche for NASA DEVELOP to get involved. It was sometime during 2014 when Cynthia Schmidt, a longtime environmental scientist working at NASA, heard about these concerns from her colleagues at the Navajo Nation. Schmidt, who shepherded NASA DEVELOP at the Ames Research Center during its inception as a student internship initiative, realized that the DEVELOP program — essentially a flexible, applied-science “A-Team” called upon to solve a variety of community and policy questions — could work with the Nation to create an improved drought assessment solution.

NASA frequently applies precipitation data from its Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) and Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) satellite programs to drought assessments, and the DEVELOP participants were open to the challenge of transforming data and developing user-interface apps to visualize changes in precipitation and drought conditions. NASA Earth observations satellite data, which are continuously collected and typically more consistent than field station data, would offer the Navajo Nation the 30-plus years of precipitation history it needed to calculate its SPIs.

It seemed like a good match.

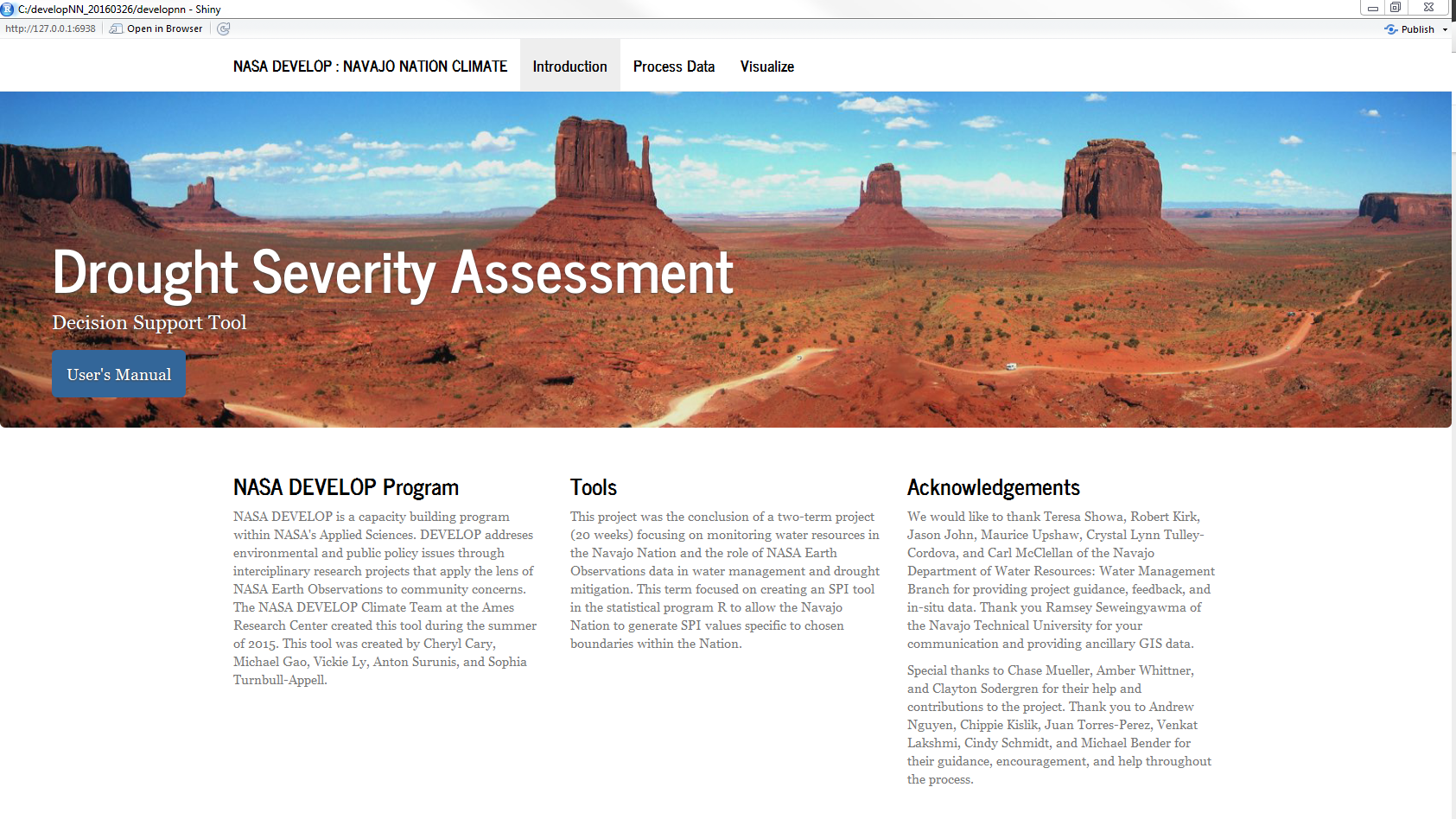

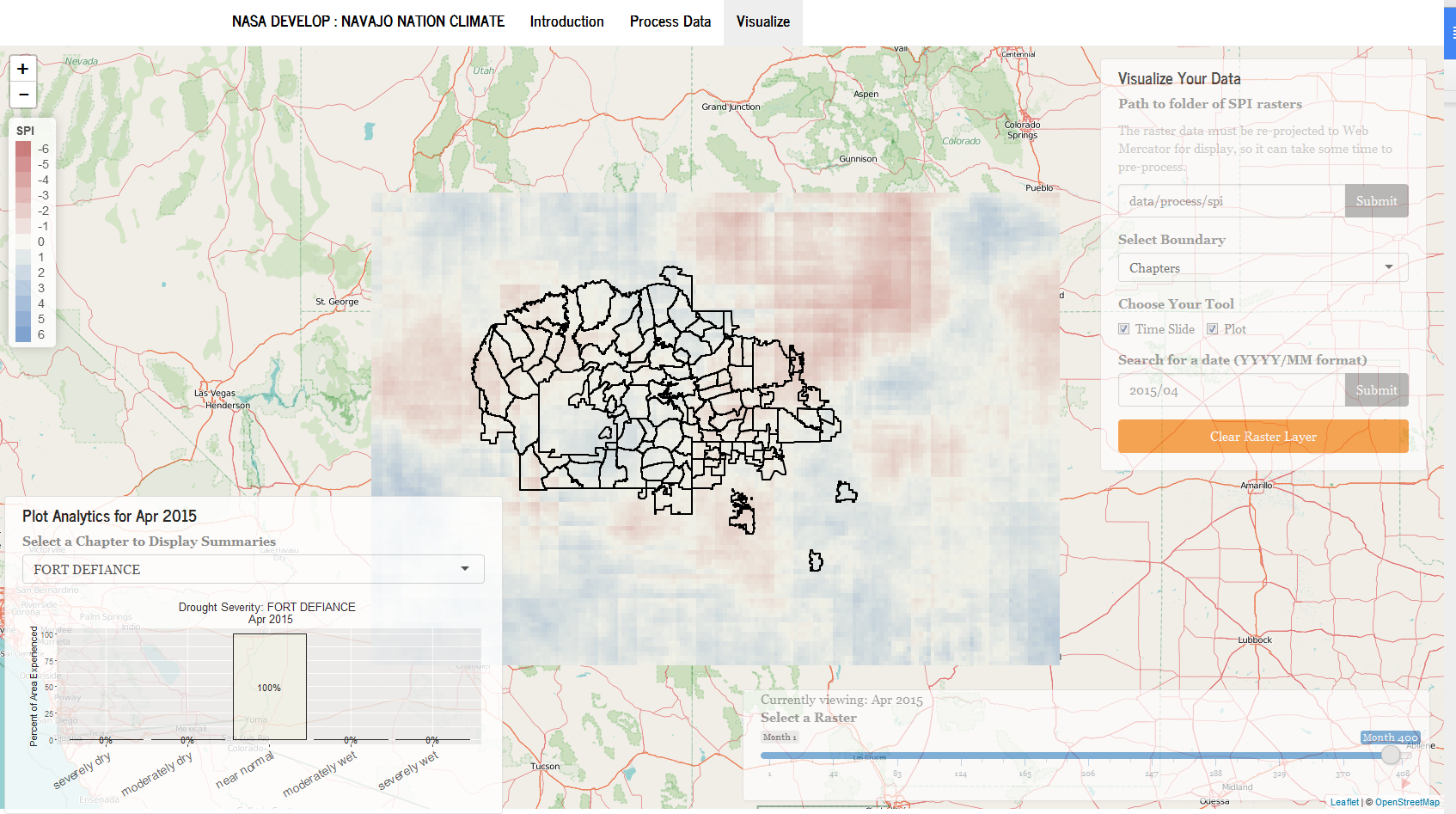

A preview screenshot of the eventual Drought Severity Assessment Tool created by NASA DEVELOP with the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources. Image courtesy of NASA DEVELOP.

Harmony

However, the working relationship between the DEVELOP team and Navajo Nation hydrologists didn’t quite blossom immediately, recalls Vickie Ly.

“When you’re working remotely, it’s especially hard to jump in-depth into a conversation,” says Ly. She and her team members were located in California, and could not visit and experience the Navajo landscape firsthand. Descriptions of everything happening on the ground had to be interpreted through conversations and data shared by Navajo partners during their regular conference calls.

By coincidence, around this same time Ly was inspired by an artist friend, Abby VanMuijen, to stretch her own communications palette. VanMuijen specializes in “graphic recording” — transcribing live conversations and brainstorms at conferences through doodles and illustrations, which could then be stitched together into an animation. It can be visually impactful way of bringing a thought process back to life, displaying all the nuances discussed.

Ly wondered if she could use the same technique to sketch out the DSAT design process, and create some public outreach videos in one stroke. Team lead Cheryl Cary was equally intrigued, and soon, Ly was slinging paint and paper, and calling up Theresa Showa, Robert Kirk, and her own DEVELOP colleagues to help narrate the videos — after convincing everyone that any tongue-tied bloopers could be easily edited out.

Unintentionally, the very process of creating these videos — picking colors and figures to portray the Navajo landscape and the data constraints, and having fun creating a shared story — brought new clarity and warmth between the DEVELOP and Navajo Nation teams.

“In some ways, working on the videos really helped us break out of the formalities,” Ly says. “Once we broke out into normal conversation, it helped us understand the landscape and their day-to-day operations.”

Of course, the videos also turned out to be beautiful storytelling devices that team members could use to quickly explain the DSAT project to new audiences. “Theresa Showa and I have formed a close relationship now,” says Ly. “She has told me that whenever someone is visiting their office or is trying to explain the project, she sends them the videos we made.”

A preview screenshot of the eventual Drought Severity Assessment Tool created by NASA DEVELOP with the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources. Image courtesy of NASA DEVELOP.

Clarity

As designed, DSAT will offer water manager three functions. First, they can calculate SPI values of their choice, using Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station data (CHIRPS), a 30-plus-year rainfall dataset. CHIRPS was ultimately chosen to sidestep the messy complexities of transforming TRMM, GPM, and PRISM into a single, coherent rainfall dataset, akin to “taking three cookie cutters and trying to make them into one shape,” as Ly puts it, though she still holds out hope to test those datasets in future versions.

Second, DSAT lets users calculate SPI values for the administrative divisions that the Navajo Nation bases its policies on — agency and chapter boundaries — exactly what McClellan and other water managers have requested. DSAT also lets users compare SPI values across ecological boundaries, such as watersheds and ecoregions — important for assessing drought conditions for natural resource management.

For an administrative region like the Chinle Navajo Agency, users can even perform a function called “plot analytics,” in which the user selects a specific month and region, and the system automatically calculates what proportion of the region was experiencing severely wet to severely dry weather during that month. This allows users to drill deeper into precipitation nuances, revealing, for example, that an area is 85 percent normal, but 15 percent dry.

“That feature was something the Navajo team recommended,” says Ly. “Once we had the visualization feature and could see the data, we could move on to the ‘you know what’d be really great to have…’ requests — and that sort of catapulted us into having more back-and-forth in developing the DSAT tool and its applications.”

Third — and with rather poetic symmetry to the YouTube videos created at the start of the project — DSAT lets users visualize SPI data as time-lapsed animations. A time chronology button lets the user animate changes in wetness and drought across the Navajo Nation territory — blue being wet, red being dry — watching the map come alive with color over different months, seasons, years, and decades.

“This function is really the bread-and-butter and the cherry on top,” Ly says, proudly.

Unity

Two rounds of funding exhausted and several months of work later, DSAT remains unfinished, but it’s getting closer. Vickie Ly and others continue to develop the code package for publishing via GitHub, refining the product in their spare time.

Carl McClellan, the Navajo hydrologist, was pleased with the progress made given the time allotted, and with the availability of DEVELOP participants to discuss issues with the software and work through improvements. “We are pursuing grant money through the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs and some climate change funding to get more resources to finish the project,” McClellan says. “That’s where we currently stand. There’s still a lot of work to be done.”

McClellan is hopeful that in the future, advances and innovations in water management also will come from within the Navajo Nation. “As time moves forward, I’m starting to see more and more students in Navajo and Native American nations pursuing careers in hydrology and engineering,” he says.

Navajo Nation hydrologist Theresa Showa (left) and NASA DEVELOP scientist Vickie Ly finally meet face to face. Image courtesy of NASA DEVELOP.

For Vickie Ly, working directly with end users such as Showa and McClellan made all the difference in the design process. “I would always ask Carl about how he plans to use the tool. I’d ask him a little more about how he might apply to decision-making and the month-to-month, and how it will change this work,” says Ly. “And he’s the one coming out of left field with these ideas on how to apply DSAT to [the Nation’s decisions] and even beyond the Navajo Nation.”

While the collaborators await DSAT’s completion, at least one other milestone was reached: Vickie Ly got to see the landscape she had only seen from the tip of her paintbrushes and GIS raster files, and meet the people she had only known through teleconference calls.

In April, the remotely based, remote-sensing scientist-artist flew out to the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources office in Window Rock, Arizona. She would present the status of DSAT to-date, finally meeting Theresa Showa and others face-to-face, smile-to-smile.

Ben Young Landis is a freelance science communicator and a contributing writer for Creative Science Writing and the Thriving Earth Exchange.