Apply now to join our next cohort of Community Science Fellows and Community Leads!

Logo courtesy of CLASH.

Identifying the barriers to testing children for lead poisoning will inform messaging to families and child care providers and will complement the policy advocacy by Cleveland Lead Advocates for Safe Housing. Increased testing will lead to early interventions that will minimize the toxic impacts of childhood lead exposure and will help to identify sources of lead hazards that require remediation.

Cleveland Lead Advocates for Safe Housing (CLASH) is an all-volunteer advocacy coalition focused on ending lead poisoning in Cleveland, Ohio. Their five years of organizing have resulted in the passage of an ordinance that requires landlords to certify their pre-1978 rental properties as lead-safe, the commitment of the Mayor to appoint a Lead Czar to his cabinet, and the purchase of a mobile lead testing van. CLASH has built its credibility on grassroots organizing and mobilization, direct action over academic planning and promotion of fact-based interventions.

One of CLASH’s four active teams is focused on expanding childhood lead testing. Lead poisoning is a known crisis in Cleveland: 14.2% of children under the age of 6 tested for elevated blood lead levels in 2014 (based on the outdated ≥5 μg/dL standard. These percentages would be higher by the current standard of ≥3.5 μg/dL). As a comparison, Cleveland’s rate of elevated blood lead levels is double the rate of Flint, MI. However, testing in the city has declined since 2016, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Testing young children is vital to understanding the scope of lead poisoning and to targeting interventions that mitigate the effects of lead exposure.

Children affected by lead poisoning are more likely to be poor, African American, and living in older housing stock. Cleveland, Ohio is one of the poorest metropolitan areas in the United States, with a population that is majority Black / African American and a childhood poverty level of 48%. Most residents live in rental housing which was built before 1978, the date at which lead paint was banned for residential use. In addition to lead paint, Cleveland has other sources of lead including the legacy of industry and leaded gasoline (pre-1985). Cleveland also has one of the highest crime rates in the U.S., which has been linked to lead poisoning in children and resulting brain developmental damage.

CLASH seeks to identify the barriers in testing children for lead poisoning so that CLASH may address them in messaging to families, child care providers, and health professionals. In addition, CLASH will advocate for systemic changes to the testing protocols and testing delivery systems that are available to families in response to identified barriers.

The CDC has determined that there is no safe level of lead exposure. Children under the age of 6 are at the greatest risk for health problems caused by lead poisoning. Childhood lead poisoning contributes to lifelong neurological and developmental damage to the brain and nervous system, which can result in lower IQ as well as learning and behavior problems. Ohio has over double the rate of elevated lead blood levels in children (5.2%) than the national rate (1.9%), with Cleveland having the highest rates in Ohio.

While the COVID-19 pandemic is blamed for a reduction in childhood lead testing across the country, in Cleveland, testing has been declining since 2016. In response to advocacy by CLASH, the City of Cleveland has committed to deploying a mobile testing van in Fall 2022. However, a similar program in Detroit in 2021 identified a lower than expected utilization rate in low income communities.

CLASH is interested in working with a scientist who can help design and evaluate a variety of qualitative tools including surveys, deep canvassing, and focus groups to help CLASH identify and overcome perceived barriers by parents, child care providers, and health professionals. Questions to explore include but are not limited to: “Who are trusted messengers?”, “Are parents/child care providers concerned about being held liable for elevated blood levels?”, and “ What policies/wrap around services can alleviate concerns?”.

This research would inform subsequent CLASH messaging and outreach around child lead testing to families and parents. In addition, conclusions would be disseminated through op-eds in local newspapers and presentations at city council meetings. CLASH will share results and insights with the Lead Safe Cleveland Coalition (LSCC) which is planning to use a public relations approach to motivating child care providers. Another potential collaboration could involve the Greater Cleveland Water Equity Partners, which is seeking citizen involvement in Lead Service Line replacement program.

Work will begin as soon as possible (April/May 2021). The exact length of the project will be determined by the needs of the community in partnership with community scientist, though we anticipate a 12-month duration.

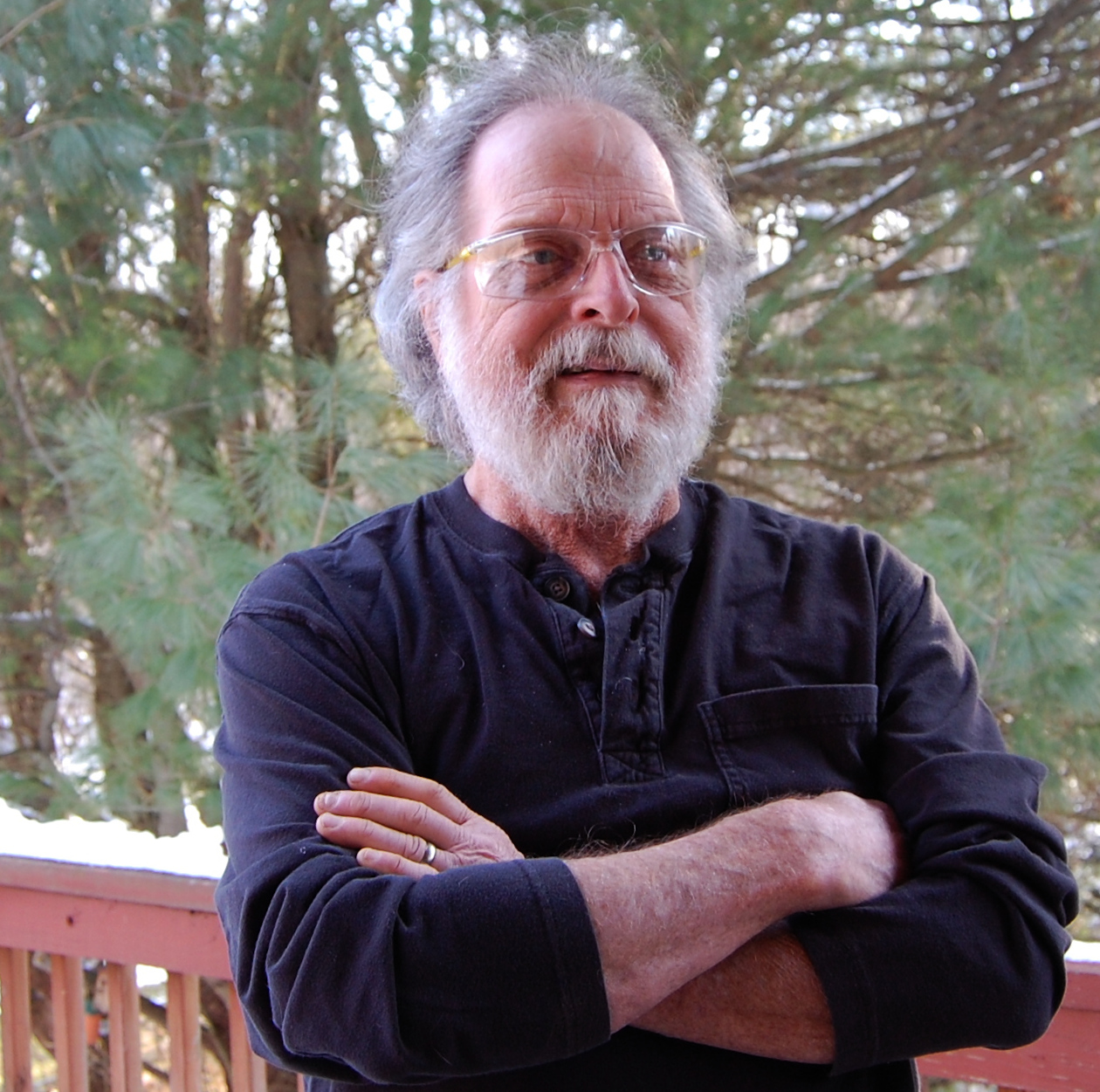

Spencer Wells is a co-founder of the CLSN. Before he retired, Spencer was director Cleveland Tenants Organization and later the tenant outreach director for the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio. Spencer is Treasurer of the Board of Directors and manages the organization’s communications.

Erika Jarvis-Jones is a community leader in the Glenville neighborhood and a survivor of childhood lead poisoning. Erika is Team leader of the Child Lead Testing Team.

Lila Parker is a public relations professional and secretary of CLASH

Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta, M.P.A., Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of Environmental Science and Public Health at the University of Arizona. Using an environmental justice framework and participatory research methods, she investigates exposure pathways and communication strategies to translate environmental health research to action and achieve structural change.

William Borkan, M.S., is a Research Scientist in the Department of Environmental Science at the University of Arizona. They coordinate community-based participatory research projects in mining-impacted communities using an environmental justice framework to engage diverse stakeholders and increase environmental health literacy. Their research interests include the study of subsurface hydrology and geochemistry of contaminated waste sites, especially those impacted by uranium contamination.

Sheelah Bearfoot is a program manager at Anthropocene Alliance. She graduated with a degree in Genetics and Plant Biology from UC Berkeley in 2016. She’s Chiricahua Apache, and worked at the Native American Health Center in SF for two years as a diabetes educator before starting an MHS in Environmental Health Science at Hopkins, where she continued her focus on Indigenous health disparities.

Ciaran Gallagher is a Ph.D. student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her research lies at the intersections of climate change, air quality, public health, and environmental justice. Previously, Ciaran has worked for state and local governments on climate change mitigation and resilience.

Anthropocene Alliance (A2) has more than 100 member-communities in 35 U.S. states and territories. They are impacted by flooding, toxic waste, wildfires, and drought and heat — all compounded by reckless development and climate change. The consequence is broken lives and a ravaged environment. The goal of A2 is to help communities fight back. We do that by providing them organizing support, scientific and technical guidance, and better access to foundation and government funding. Most of all, our work consists of listening to our frontline leaders. Their experience, research, and solidarity guide everything we do, and offer a path toward environmental and social justice.

(c) 2024 Thriving Earth Exchange