Measuring and Monitoring the Effects of Greening on the Urban Heat Island Effect, Water Uptake, and Social Challenges

Louisiana, New Orleans, United States,

Photo courtesy of Healthy Community Services

Results

Project Title: Measuring and Monitoring the Effects of Greening on the Urban Heat Island Effect, Water Uptake, and Social Challenges

Location: New Orleans, LA (7th Ward)

The Team:

- Angela Chalk, Executive Director, Healthy Community Services, [email protected]

- Yasmin Davis, New Orleans Community Manager, ISeeChange

- Julia Kumari Drapkin, CEO, ISeeChange, [email protected]

- Amy Lesen, Research Associate Professor, ByWater Institute, Tulane University, [email protected]

- Evan Mallen, Graduate Student, Georgia Tech, [email protected]

- Brian Stone, Director, Urban Climate Lab, Georgia Tech, [email protected]

- Derek Van Berkel, Assistant Professor of Data Science, Geovisualization and Design, School for Environment and Sustainability, University of Michigan, [email protected]

The project team would also like to recognize the efforts of Neighborhood Champions and ISeeChange staff for making this project possible.

The Initial Challenge:

Healthy Community Services (HCS) sought to partner with scientists to measure and monitor the effects of the placement of trees and rain gardens, as well as measure the effect of tree plantings on the heat island effect, to assess how the organization’s greening activities are improving the community. HCS also sought to concurrently partner with a social scientist who can carry out research to help link these environmental programs to possible social outcomes. An important part of the project was educating the community about these programs and their environmental and social effects. This work would then inform HCS’s greening activities and future efforts for tree plantings and rain garden placement. Involvement of the residents in this work would increase ownership and community engagement. Desired outcomes were reduction in the heat island effect, localized flooding, and crime, as well as improved air quality. HCS envisioned that the community would benefit from the project as they beautify and improve the health of their environment, and learn about new data sources and resources for greening and green infrastructure.

The Methods

This project involved a large team working on a multi-faceted project. While all participants contributed to discussion and decision-making regarding the project as a whole, the team would often divide tasks and responsibilities, using monthly telecons to update everyone on activities and “sub-group” conversations. On average team members committed 3 hours a week on fund procurement, data analysis and collection and community deliverables (e.g. flyers, presentations)

Google Drive was heavily relied on to track notes and store files. Files include literature, photographic visualizations of the community, remotely sensed data, spatial datasets, community survey results and temperature monitoring data. This was obtained through online academic libraries, community photographs manipulated using photoshop, spatial data repositories, a door-to-door community survey, and our own network of temperature monitoring sensors.

This project was supported, in part, by funding from the Tulane University Center for Public Service Community Engaged Research Program. Healthy Community Services also contributed funding to purchase heat sensors.

The Results

While it has inspired several collaborations among members of the project team, this project was primarily comprised of two complementary, parallel initiatives:

- A community survey to learn about neighborhood preferences and attitudes regarding rain garden design and tree plantings

- Deployment of a network of heat sensors in the community to assess the relationship between tree cover and heat.

7th Ward Community Survey

[caption id="attachment_21869" align="alignright" width="300"] Yasmin Davis, ISeeChange, speaks with a resident. Photo courtesy of ISeeChange.[/caption]

Yasmin Davis, ISeeChange, speaks with a resident. Photo courtesy of ISeeChange.[/caption]

After extensive development and refinement, logistics planning and securing IRB approval, the team launched a community survey in July. The survey was conducted by a team of Neighborhood Champions, Tulane University students, and volunteers from iSeeChange, who were trained and supported on-the-ground by Angela, Amy, Julia and Yasmin, and remotely by Derek. The surveyors went door-to-door in groups of 2, with each group assigned 1-2 blocks in the 7th Ward neighborhood. The survey was conducted on tablets using the ODK Collect app while offline. Once reconnected to the internet, the survey results could then be pushed to a Google Sheet. Through their methods, preparation and analysis, the team took care to maintain the privacy of personal data.

Ultimately 47 people were surveyed – the team learned that

- An approximately equal number of residents own their homes as rent.

- 57% of residents are native to New Orleans

- Nearly everyone is in favor of planting trees in the neighborhood, but there are preferences in terms of species. Red Maple, for example, is much more popular than Savannah Holly.

- 72% of neighbors are willing to plant trees on their property, 64% would host a rain barrel, and 57% would be interested in a rain garden

- Residents also provided recommendations for where to plant trees generally, and they acknowledged that they perceive the 7th Ward as having less green space than other New Orleans communities.

When asked how beautiful their neighborhood is compared to others in New Orleans, the collective response was a 6.4/10. The survey asked about reactions to neighborhood improvements like rain gardens, community gardens, and community art (all very popular), and what beautiful features already exist in the neighborhood (answers included historic buildings, community space, public art, green space, and the people themselves.)

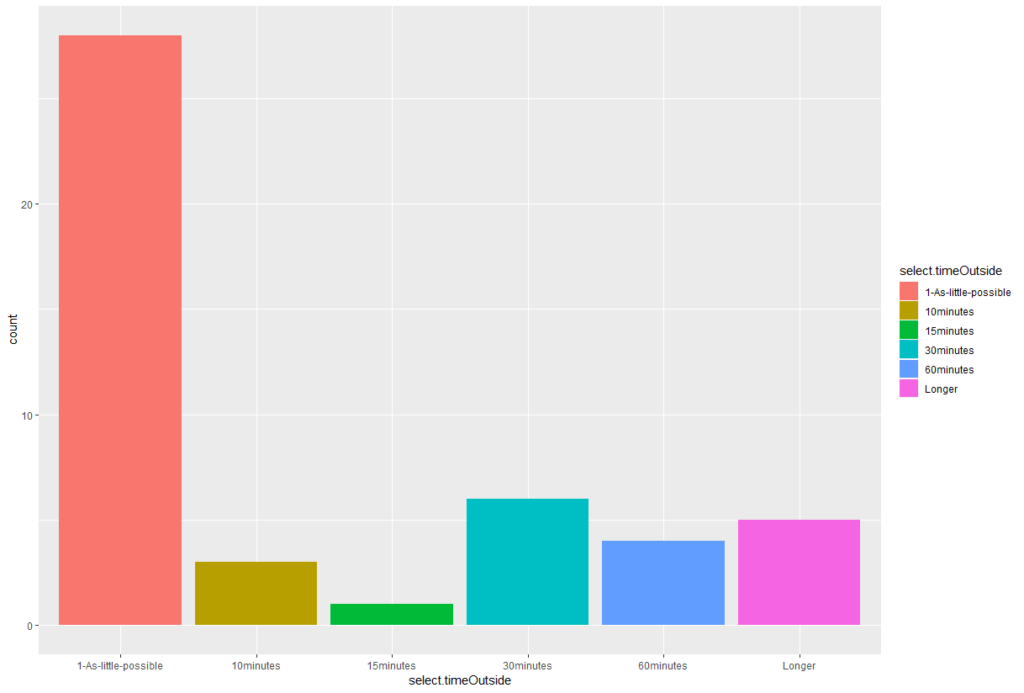

The survey also asked about heat, a known health issue in the community, and one that also affects the fabric of the neighborhood itself. Many residents have been affected by respiratory illness, hypertension, and heat stroke. They also change their behavior on hot days (see Figure 1).

[caption id="attachment_22480" align="aligncenter" width="700"] FIgure 1: Time spent outside on hot days. Most people spend as little time as possible outdoors when temperature is high.[/caption]

FIgure 1: Time spent outside on hot days. Most people spend as little time as possible outdoors when temperature is high.[/caption]

The information learned from this effort will help outreach and planning efforts by Healthy Community Services in years to come. It provides direction in how to prioritize tree plantings and green infrastructure initiatives for maximum community benefit. It also contributes urgency to local greening and cooling efforts, and provides scientific insight into exactly how residents are affected by heat and community characteristics, and at what rates.

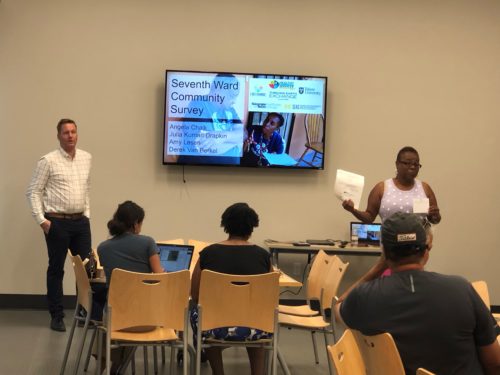

[caption id="attachment_22488" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Derek and Angela speak to community members during a September 20, 2019 community meeting[/caption]

Derek and Angela speak to community members during a September 20, 2019 community meeting[/caption]

Heat Sensor Network

Early in the project, Brian and several of his students visited New Orleans as a planned trip for a graduate course titled “Climate Change and the City.” While in New Orleans, they were able to meet with Angela in person and walk the neighborhood to learn about priority areas of concern and community features. One student prepared a Resiliency and Adaptation Plan for the community which included block-by-block maps detailing flood exposure, heat exposure, and sensitive populations. It also proposed several design-based strategies that could reduce heat and flood risk in high-priority areas. This report itself, shared with the community, was an incredibly valuable resource – it also fed into longer-term planning efforts to deploy a network of on-the-ground heat sensors to compliment the satellite data used in the initial study.

Following this early success, the team worked for several months to acquire funding to bring this network online. They eventually secured funding in Summer 2019 from Tulane University’s Center for Public Service (this grant funded the survey as well), with additional support from Healthy Community Services’ board of directors. With this funding and in-kind support from the scientific partners, the project team was able to deploy a network of 10 temperature and humidity sensors at strategic locations in the community. Locations were chosen to capture a diversity of land-cover patterns (e.g. greenspace, young vs. mature trees, and impervious surfaces.) while maintaining a strong signal. These sensors will monitor how temperature and humidity vary with different land cover patterns through at least Summer 2020 – longer pending additional funding.

[caption id="attachment_22490" align="alignright" width="350"] Installing heat sensors in the 7th Ward[/caption]

Installing heat sensors in the 7th Ward[/caption]

Of the 10 sensors, 2 were HOBO sensors and the remaining 8 were prototypes developed by ISeeChange and their partners as part of a multi-community heat mapping initiative led by the organization. While the HOBO data will need to be retrieved manually, the remaining sensors transmit data real-time via a gateway hub located at Angela’s house. Pending a platform upgrade (in progress as of November 2019) this information will be visible on ISeeChange.org and its suite of mobile apps for use by the community in real time. Community members will be able to monitor and compare the heat and humidity at different points in the community real-time using the web interface. Because of the nature of ISeeChange.org’s platform, community members will also be invited and encouraged to contribute their lived experiences alongside this data to present a rounded, nuanced story of heat, trees, and community health.

In addition to community engagement and empowerment through awareness regarding heat in the community and ability to share a narrative regarding that heat, the data from the sensor network will also support Healthy Community Services tree planting efforts. Data over time comparing the difference on the street between young and mature trees – and locations where no trees are present – will contribute to the community organization’s efforts to fundraise and secure donations of additional trees.

[caption id="attachment_22491" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Julia (center) and ISeeChange staff after the successful installation of a heat sensor[/caption]

Julia (center) and ISeeChange staff after the successful installation of a heat sensor[/caption]

What Comes Next

Upcoming plans for this team include:

- Observation and communication of data from the sensor network over the next year (All; Julia, Brian and Evan will be leading the analysis and handling of raw data)

- Development of a manuscript to document and share the methodology developed for the community survey. The team feels that this effort will help other community-scientist teams conduct similar work. (Led by Derek and Amy)

- Pursuing additional funding to continue the existing monitoring and extend the network further (All)

- Cross-linking learning from the sensor deployment process and prototype development with other community heat monitoring initiatives including the Bronx and elsewhere, including other neighborhoods in New Orleans (Julia/ISeeChange).

Reflections

Things that contributed to their success:

- The team did an exceptional job of recognizing and organizing the contributions of multiple partners and navigating the nuances (and sometimes quirks) of their home institutions. The project team operated within community, nonprofit organizations, universities and the federal government

- Early on, Derek took responsibility for taking notes and distributing agendas for monthly calls. His facilitation and record-keeping ensured that each project component was discussed at team meetings and that everyone had notes and a shared document storage space.

- The team effort to procure funding (this is ongoing) was likewise an important factor in the success of the project. These funds enabled us to conduct the surveys and install the heat monitoring units

- The success of the project was moreover related to existing local capacity. Angela is a committed and dedicated resident of the 7th Ward that actualized community outreach through involving community members (i.e. community champions). Her network was an invaluable resource to the project.

- Finally the commitment of additional local partners was key to the success of the project. ISeeChange and Julia added much needed on-the-ground resources that ultimately made this project a success. This was a situation where the project and ISeeChange gained mutual benefits with bidirectional learning and capacity building. The science volunteers added experience and efforts in research design, while ISeeChange brought experience in the practice of community-based projects.

Things they might do differently if they were to do it over again:

- While a great experience for all, at time there was tension between the different interests of the participants. For example, the scientist volunteers’ obligation to produce scientific outputs may not always align with local goals, and partners sometimes have larger interests beyond our specific community.

- A funding structure that compensates all stakeholders may alleviate the pressures of such projects and demonstrate the commitment to local efforts/interest. For example, community projects could be funded (e.g. portion of tree planting) in equal proportions to research. This would diminish the pressure on scientists to formulate scientific outputs and give much-needed resources for actionable results at the community level

Advice for people pursuing similar community science projects:

- This project remained in a planning phase for some time, in large part due to a need for funding. Once funding was secured, the team’s progress accelerated significantly. When planning a project, build in impactful work and early successes that can be achieved solely with resources at hand.

- When working in large teams, it’s especially important to ensure adequate opportunity for everyone to contribute during meetings and to recognize organizational requirements and sensitivities.

[caption id="attachment_22492" align="aligncenter" width="450"]

(L-R) Derek, Angela, Amy, and Barrett (Friend of Thriving Earth Exchange)[/caption]

(L-R) Derek, Angela, Amy, and Barrett (Friend of Thriving Earth Exchange)[/caption]

Description

The 7th Ward is an historically black neighborhood in New Orleans, home to over 10,000 residents, 87 percent of whom are African American. The 7th Ward plays an important role in the history and culture of New Orleans and its African American community, being a historical center for New Orleans Creoles, a working-class neighborhood that was especially known for skilled laborers in the building trades. The 7th Ward has rich cultural institutions such as social aid and pleasure clubs, St. Augustine High School, Mardi Gras Indian tribes, musicians and artists, as well as faith-based institutions. There are a large number of long-term residents and families in the neighborhood, and a growing population of new residents and Hispanic residents. The 7th Ward Healthy Community Services organization is committed to providing residents of vulnerable communities with the knowledge to improve their quality of life by reducing and/or eliminating the negative factors of the social determinants of health.

The 7th Ward neighborhood faces a number of challenges, including gun violence, repetitive flooding, drug proliferation, post-Katrina blight, gentrification, and access to quality housing. The 7th Ward has a 10-14 percent higher poverty rate than New Orleans as a whole. The residents and the 7th Ward Healthy Community Services (HCS) organization are particularly concerned about greening in the neighborhood, following studies that have shown, for example, that neighborhoods with trees have 35 percent less domestic violence. The “urban heat island effect” impacts the health of the vulnerable residents in the 7th Ward community, and the youth and elderly suffer from chronic illnesses such as diabetes and asthma. Communities of color and low-income/working class residents of the neighborhood are affected by lost wages from evacuation due to natural disasters and the interruption of daily life due to repetitive flooding. The HCS has existing tree-planting and rain barrel/rain garden programs in the 7th Ward neighborhood but wants more information about the effectiveness of these programs as well as the intersection between the environmental and social challenges facing the community. The HCS has identified an ongoing need for green infrastructure to reduce or mitigate repetitive flooding, for increased tree cover in the neighborhood to address the urban heat island effect, and for research that measures the success of these initiatives and links them with social change and wellbeing.

The Project

The HCS is partnering with scientists to measure and monitor the effects of the placement of trees and rain gardens (for example, measure the water uptake of trees and rain gardens), as well as measure the effect of tree plantings on the heat island effect, to assess how the organization’s greening activities are improving the community. The HCS would also like to concurrently partner with a social scientist who can carry out research to help link these environmental programs to possible social outcomes. An important part of the project will be educating the community about these programs and their environmental and social effects. This work will inform the HCS’s greening activities and future efforts for tree plantings and rain garden placement. Involvement of the residents in this work will increase ownership and community engagement. Desired outcomes are reduction in the heat island effect, localized flooding, and crime, as well as improved air quality. The HCS envisions that the community will benefit from the project as they beautify and improve the health of their environment, learn about new data sources and resources for greening and green infrastructure.

Desired outputs of the project are:

- A GIS database to track the efforts of tree-plantings and rain gardens

- Precipitation and flooding analysis combined with water uptake analysis of trees and rain gardens

- A methodology for continued mapping and monitoring

- A time series of tree canopy and air temperature (and perhaps an interactive tool that can continue to be used by the community)

HCS will use this information to share with community members, other stakeholders, and will work with the city to further these neighborhood environmental programs.

Project Updates

Images of Change

During AGU’s 2021 Fall Meeting in New Orleans, we were honored to meet many community members who are working to make the region’s neighborhoods healthier, more connected and more resilient. Here’s a glimpse of what we saw.

Community lead Julia Kumari Drapkin stands in front of a football field in Gentilly, now the site of a water retention project. The community-sourced data from the Gentilly Thriving Earth Exchange project was a catalyst that resulted in remodeling and reallocation of $4.8 million in flood mitigation to the St. Bernard Campus in Gentilly. The underground unit was expanded by 2.5x, storing up to 5 million gallons of stormwater in underground detention basins – the largest of its kind in the South.

Community lead Julia Kumari Drapkin stands in front of a football field in Gentilly, now the site of a water retention project. The community-sourced data from the Gentilly Thriving Earth Exchange project was a catalyst that resulted in remodeling and reallocation of $4.8 million in flood mitigation to the St. Bernard Campus in Gentilly. The underground unit was expanded by 2.5x, storing up to 5 million gallons of stormwater in underground detention basins – the largest of its kind in the South.

A view of Pumping Station No. 3 in the 7th Ward. Flood control infrastructure is critical in New Orleans 24/7 – there’s someone on the job at every pumping station in the city at all hours, every day, 365 days a year. Here, we see the canal and the transfer pipe that moves water out of the neighborhood and pumps it to Lake Pontchartrain.

A view of Pumping Station No. 3 in the 7th Ward. Flood control infrastructure is critical in New Orleans 24/7 – there’s someone on the job at every pumping station in the city at all hours, every day, 365 days a year. Here, we see the canal and the transfer pipe that moves water out of the neighborhood and pumps it to Lake Pontchartrain.

AGU Design director Beth Bagley photographs Angela Chalk, founder of Healthy Community Services, in front of a bus shelter designed with a slanted roof and rain garden to reduce flooding. It also includes a solar-powered charging station that residents can use to power up electronics – a valuable resource if power is lost due to hurricanes or other climate catastrophes. Angela Chalk served as community lead on a Thriving Earth project on monitoring the effects of greening on the urban heat island effect, water uptake, and social challenges and is serving as a Community Science Fellow on a new project in the 7th Ward.

AGU Design director Beth Bagley photographs Angela Chalk, founder of Healthy Community Services, in front of a bus shelter designed with a slanted roof and rain garden to reduce flooding. It also includes a solar-powered charging station that residents can use to power up electronics – a valuable resource if power is lost due to hurricanes or other climate catastrophes. Angela Chalk served as community lead on a Thriving Earth project on monitoring the effects of greening on the urban heat island effect, water uptake, and social challenges and is serving as a Community Science Fellow on a new project in the 7th Ward.

The Flooded House Museum at the breach site of the London Avenue Canal flood wall is a sobering reminder of the impacts of Hurricane Katrina. During the storm, the house was pushed across the street and turned around 180 degrees. Today, it has been returned to its original plot, and is preserved as a museum where visitors can look in through storm windows to see how the hurricane devastated its interior. The London Avenue Canal’s flood wall can be seen in the background; the wall was breached just yards from where the house stood.

The Flooded House Museum at the breach site of the London Avenue Canal flood wall is a sobering reminder of the impacts of Hurricane Katrina. During the storm, the house was pushed across the street and turned around 180 degrees. Today, it has been returned to its original plot, and is preserved as a museum where visitors can look in through storm windows to see how the hurricane devastated its interior. The London Avenue Canal’s flood wall can be seen in the background; the wall was breached just yards from where the house stood.

Community lead Beth Butler and resident Debra Campbell stand at the corner at the site of a future bioswale and affordable housing in New Orleans’ 8th Ward. The planned design integrates native plant gardens and private outdoor space to promote residents’ physical and mental health as part of the Thriving Earth projects Designing Bioswales for Improved Air Quality, Serenity and Reduced Flood Risk and Assessing Flooding and Hydrodynamics for Community Revitalization.

Community lead Beth Butler and resident Debra Campbell stand at the corner at the site of a future bioswale and affordable housing in New Orleans’ 8th Ward. The planned design integrates native plant gardens and private outdoor space to promote residents’ physical and mental health as part of the Thriving Earth projects Designing Bioswales for Improved Air Quality, Serenity and Reduced Flood Risk and Assessing Flooding and Hydrodynamics for Community Revitalization.

Community leads Amy Stelly and Tamah Yisrael pointing out the I-10 corridor in the 7th Ward, New Orleans. Their organization, Claiborne Avenue Alliance, worked with Thriving Earth Exchange to evaluate the impacts of Highway I-10 that runs above Claiborne Avenue. Their work contributed to a national conversation with New Orleans at its center.

Community leads Amy Stelly and Tamah Yisrael pointing out the I-10 corridor in the 7th Ward, New Orleans. Their organization, Claiborne Avenue Alliance, worked with Thriving Earth Exchange to evaluate the impacts of Highway I-10 that runs above Claiborne Avenue. Their work contributed to a national conversation with New Orleans at its center.

Visiting flood-affected homes in the 9th Ward, New Orleans, with community lead Beth Butler. Raising homes on stilts like this protects them from floods; the lot next door will be developed into a rain garden and bioswale to provide further flood protections and beautify the neighborhood.

Visiting flood-affected homes in the 9th Ward, New Orleans, with community lead Beth Butler. Raising homes on stilts like this protects them from floods; the lot next door will be developed into a rain garden and bioswale to provide further flood protections and beautify the neighborhood.

Project Team

Community Lead

Angela M. Chalk is a 4th generation 7th Ward resident. As she puts it “I’m proud to say I live in a house that my Grandpa won in a card game in 1942.” The legacy her family instilled in her is to remain committed spiritually to God and to do right by her neighbors and the community.

Currently, she serves as President 2017-2018 for the Louisiana Public Health Association; former Secretary of the 5th District Police Community Advisory Board, (PCAB); a Foundation for Louisiana LEAD to the COAST Cohort Fellow; a Global Green Water Wise Champion Designee; and is Executive Director of Healthy Community Services, a non-profit organization she founded in order educate residents and improve health outcomes regarding the social determinants of health. Healthy Community Services is a community based outreach and health education provider.

Angela is a strong advocate and helps to teach neighbors about incorporating Green Infrastructure solutions to reduce street flooding. She works closely with Global Green, USA and Water Wise. Her goal is to improve the quality of life for the residents of her community by her desire to serve, whether it is informing neighbors and residents about Green Infrastructure, working with the homeless, reducing crime, providing access to healthy food sources or increasing awareness about public health issues that affect residents. Also, Ms. Chalk serves on the Board of the Treme’/7th Ward Cultural District.

Angela recently retired from the Louisiana Department of Health & Hospital after 31 years of service. In that role she determined Medicaid eligibility for uninsured populations within a 3 parish area. She was assigned the task as Team Leader for “Healthy Louisiana” (the Medicaid Expansion Program). In that role she oversaw and coordinated the efforts to enroll uninsured persons who reside in Orleans, Jefferson and St. Bernard parishes.

She previously served as the New Orleans Regional Medicaid Outreach Coordinator. In that capacity, she was responsible for outreach activities to enroll uninsured children to the Louisiana Children’s Health Insurance Program, (LaCHIP). The area of responsibility included Orleans, Jefferson, St. Bernard and Plaquemines parishes. Angela developed an outreach training program used to provide guidelines for employees participating in outreach events.

In addition to her primary duties, Angela represented the LA DHH in conjunctions with the United States Department Housing and Urban Development as the liaison for Medicaid enrollment for homeless populations. The program, “New Orleans: Dedicated to Ending Homelessness” is a U. S. Presidential Initiative to end homelessness. In this capacity she attends “Homeless Court” to determine or retain Medicaid eligibility to qualified individuals in order to eliminate barriers to receiving health care services.

Scientific Partners

Brian Stone teaches in the areas of urban environmental planning, climate change, and planning history and theory. Stone’s program of research is focused on the spatial drivers of urban environmental phenomena and is supported through funding from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. He is Director of the Urban Climate Lab at Georgia Tech. Stone’s work on urbanization and climate change has been featured on CNN and National Public Radio, and in print media outlets such as Forbes and The Washington Post. He is author of the recently published book, The City and the Coming Climate: Climate Change in the Places We Live (Cambridge University Press), which received a Choice Outstanding Academic Title Award for 2012. Stone holds degrees in environmental management and planning from Duke University and the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Derek Van Berkel is Assistant Professor of Data Science, Geovisualization and Design at the School for Environment and Sustainability, University of Michigan. His research examines the human dimensions of land cover/use change and ecosystem services at diverse scales. It aims to use spatial analysis and geovisualizations of social and environmental data and spatial thinking to develop solutions for today’s most pressing environmental challenges. He obtained his PhD from VU University in Amsterdam, researching the spatial and human dimensions of land change under the direction of Dr. Peter Verburg. This was followed by a postdoc in the Department of Geography at The Ohio State University, where he worked with Dr. Darla Munroe on amenity landscapes and land change in forest communities. Following this Derek took a postdoctoral researcher position at the Center for Geospatial Analytics (CGA), North Carolina State University with Dr. Ross Meentemeyer examining urban areas as complex coupled natural and human systems. He has contributed to the EnviroAtlas Project in cooperation with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Amy E. Lesen is Research Associate Professor in the ByWater Institute at Tulane University in New Orleans. Lesen works on the coast and in urban estuaries. The overarching theme of her work is the interrelatedness between environmental and human social dynamics in coastal cities and coastal communities, and how those systems are influenced by climate and environmental change. Most of her current work focuses in New Orleans, Southeastern Louisiana, and the Gulf Coast. Lesen also does research and writing about the intersection between science and the arts, disaster resilience, informal science learning, scientific public engagement, science communication, participatory research, and interdisciplinarity. She uses both quantitative and qualitative methodologies in her work, including surveys and oral history. She was Associate Professor of Biology Dillard University, a small Historically Black College in New Orleans from 2007 until summer 2014. Lesen has a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in Marine Fisheries Biology and a PhD from the University of California at Berkeley in Integrative Biology with a concentration in biological oceanography and paleoceanography. She joined Tulane University in September 2014. Previously, she was an assistant professor at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NYC from 2003 to 2007. Dr. Lesen was chair of the Biology Department at Dillard from 2009 to 2012.

Julia Kumari Drapkin is the executive producer and founder of iSeeChange.org. She is a radio, television, and multimedia producer based in New Orleans with a passion for finding innovative ways to connect people to their environment and to each other. iSeeChange was born out of covering natural disasters and climate change science across the globe and in her own backyard. Drapkin has worked as the Senior Science Reporter for The Nature Conservancy; a foreign correspondent and environmental radio reporter for PRI’s The World and Global Post in South America; as a photojournalist for the Associated Press in South Asia and the St. Petersburg Times; and most recently as a multimedia producer for the Times Picayune.

Collaborating Organizations

ISeeChange is dedicated to empowering communities to document and understand their environment, weather and climate in order to increase resilience. ISeeChange mobilizes communities to share stories and micro-data about climate impacts to inform and improve climate adaptation and infrastructure design. Their platform, tools, and investigations provide equitable, iterative ways for residents to personalize, measure, and track climate change impacts and better participate in community adaptation decisions.

Each post is synced with weather and climate data and broadcast to the community to investigate bigger picture climate trends. Over time, community members can track how climate is changing, season to season, year to year, and understand the impacts on daily life.

ISeeChange is a strategic partner of Thriving Earth Exchange as community members use their platform and tools to better characterize, visualize, and communicate neighborhood-level climate trends and co-develop solutions to mitigate those risks.

Status:

Complete,

Location:

Louisiana,

New Orleans,

United States,

Managing Organizations:

Thriving Earth Exchange,

Project Categories:

Climate Change,

Natural Resources,

Project Tags:

No tags