A home is supposed to be a refuge – a safe place to rest in a busy, unpredictable world. But what do we do when home doesn’t feel so safe – when you find out harmful pollutants have been there for years, or even decades?

For Denver residents, this hypothetical question became real when they learned that radon, a radioactive gas, was seeping into their homes through soil and concentrating in their basements. How did they learn about the radon contamination, and what did they do about it?

Taking Neighborhood Health to Heart means listening to residents

To find out, we need to go back in time a bit. In 2006, residents in Denver concerned about community health founded Taking Neighborhood Health to Heart (TNH2H), a community-based participatory research project.

TNH2H involves five diverse Denver neighborhoods: Northwest Aurora, Central Park, East Colfax, Park Hill and Northeast Park Hill. The goal was to create a model for residents to participate directly in health and environmental research to better understand – and improve – neighborhood health.

The initiative was born out of a series of projects funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. “Researchers, community, other stakeholders were supposed to be partners and I wanted to see how that would happen,” said George Ware, a Denver resident, former supervisor of the Colorado Public Health and Environment’s STI/HIV Research and Evaluation Unit, and TNH2H’s chair. “We wanted to make sure community voice was real and not in name only.”

TNH2H was focused on topics like the social and built environments and their connections to health, physical activity among youth, and access to affordable, nutritious food, and conducted research on concerns like social connectedness among seniors. From the beginning, the project strove to make sure its data was equitable and accurately represented the community. “Folks tended to be in lower-income rental units, they weren’t represented as much in registered neighborhood organizations, and we subsequently trained other [organizations] on doing that kind of work,” said Patti Iwasaki. “We learned from each of our projects, and gathered a lot more folks of color into the organization who were interested in staying in and working with their neighborhoods.”

TNH2H started considering factors like air quality when, during their regular community conversations, “various issues of the environment came up – people started talking about [their concerns],” said Ware.

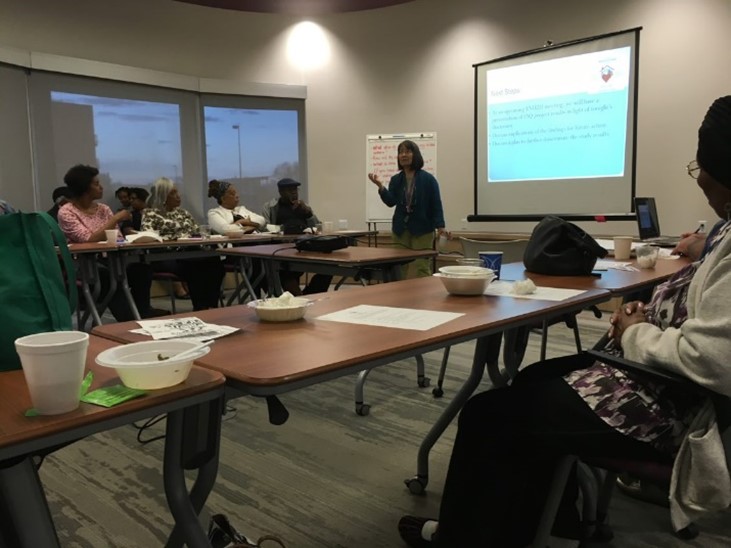

Patti Iwasaki meets with community members to discuss the indoor air quality monitoring project. Photo credit: TNH2H

Ware and Iwasaki met Thriving Earth Exchange director Raj Pandya when they co-presented on participatory research at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). Thriving Earth started working with TNH2H to outline where a community environmental health project might focus first. Through TNH2H’s conversations with residents, two concerns came to the fore: Tetrachloroethylene (usually known as PERC), and radon.

PERC is a chemical of concern known as a volatile organic compound (VOC) commonly used in dry cleaning. PERC exposure can cause eye and respiratory irritation in the short term, and studies show an increased cancer risk with long-term exposure. If not properly contained and handled, it can leak into soil, water and peoples’ homes. PERC contamination has been a major issue in Denver and spills can take years to clean up.

Radon, on the other hand, is a naturally occurring carcinogen: it’s an odorless gas that occurs from the breakdown of uranium in soil and seeps out of the ground, often settling in basements. High radon concentrations have been found in all parts of Colorado.

Examining indoor air quality in Denver

Thriving Earth Exchange connected TNH2H with Ashley Collier-Oxandale, a PhD student in environmental engineering from the University of Colorado Boulder studying indoor air quality. Collier-Oxandale met with the team, and later brought on additional support for the project through CU Engage, a university program that strives to build equitable partnerships between students and communities, schools, and organizations to address complex public challenges. With her help, TNH2H set their research priorities, as she shared in a 2018 blog for Thriving Earth Exchange: “The community was interested in several questions regarding their local air quality, so together we narrowed the questions down and planned a project.”

Collier-Oxandale suggested that the project design also focus on comparing a low-cost PERC testing technology with a higher-quality (and much more expensive) test, to see if the low-cost method was effective. If it was, it might help more residents test their homes.

A radon test used during the pilot study. Photo credit: TNH2H

“We made a strategic decision to look at radon, but our initial focus was PERC – that was the reason why we decided to test this new technology,” said Ware. “[However], we live in a state with a lot of radon, and a lot of people didn’t know about the dangers of radon – we wanted to encourage screening for [it].” TNH2H leveraged the relationships that participants already had in the neighborhood and encouraged people to talk to their neighbors about the study to encourage households to participate. The pilot study included 15 volunteer homes and the project team trained data collectors to do the sampling and answer residents’ questions. Afterward, TNH2H met individually with each of the volunteers to discuss their results, go over the data and identify potential resources for remediation.

The project’s findings were a big surprise. PERC was not present in high-enough concentrations to be a concern (and the study did not show that the cheaper PERC air quality test was as effective as the high-quality one). But radon was another story.

“What we were shocked about is that in the initial pilot study, 80 percent of homes came back with high [radon] levels,” said Iwasaki. Residents were surprised that they hadn’t heard about radon risk before. “The average number of years they lived in their neighborhood was [over 35], and they were very upset about why they had never heard from anybody about testing.” Collier-Oxandale agreed: “What was surprising was that the residents had lived there for so long, and no one had told them. This real health risk that we can test for, we have remediation methods, it’s like low-hanging fruit.”

The team presented a poster on their findings at AGU’s Fall Meeting in 2016, and the lack of information around radon was so important – and urgent – that TNH2H decided to proceed with another radon study.

As TNH2H explored how to communicate about radon, respond to residents’ concerns and help people find solutions, they made a conscious decision to focus on working with city government, rather than state officials who weren’t familiar with the community, its history and its cultural context. A state official who met with the community was “very resistant to sharing data and discouraged us from undertaking a study,” said Iwasaki. “What we decided was, we would take the high road and ally ourselves with some of our friends and folks that we know that work with the city.”

Understanding radon – and other risks

The Thriving Earth pilot study was the first of three projects exploring radon in TNH2H’s included neighborhoods. Air quality scientist David Pfotenhauer led the second project. A graduate student at the time, Pfotenhauer was involved with CU Engage and had previously studied air quality and environmental engineering in Ghana. Collier-Oxandale encouraged him to apply to join the project.

Pfotenhauer said that Collier-Oxandale created a pathway for the project’s next iteration in the community. “Ashley got a lot of that relationship building underway. As you develop trust, you can revise and evolve [projects] based on new data that you learn from other ones.” For the next iteration, David and TNH2H expanded the sampling network, doubling the number of participants measuring radon in their homes. Because “PERC was basically nil” in the previous study, residents felt comfortable taking it off the list of VOCs they were concerned about. However, residents had new questions: could products like household cleaners be emitting harmful chemicals, too?

Taking Neighborhood Health to Heart (TNH2H) participants. TNH2H chair George Ware is pictured at far left; Thriving Earth Exchange pilot study scientist Ashley Collier-Oxandale is pictured at far right. Photo Credit: TNH2H

“We added [VOCs from household cleaners] to the monitoring study,” said Pfotenhauer. “We got to give a customized report back to homeowners about VOCs in the home. Thankfully no one had dangerous levels, but it encouraged their inquiry of how what is in their homes affects their environment.” TNH2H’s adaptable, participatory and community-based research model was flexible to answer residents’ evolving questions and concerns.

“More times than not, community members were willing to just talk as I was doing the house visits and sampling procedures,” said Pfotenhauer. “[Residents would say], ‘I’m so glad this is part of a study, I don’t trust that someone isn’t going to just sell us something – we want an honest, scientific explanation what’s going on in our air.” This reveals another important part of the project – scientific research without a vendor like an HVAC or home air quality company involved helped residents feel confident that potential risks were real and needed to be remediated, without being pressured by a company that stood to make money off home improvements.

In 2017, TNH2H successfully applied for an Environmental Protection Agency Environmental Justice Small Grant to help fund a third study, which further expanded the sampling area and confirmed that radon was a significant concern for neighborhood residents.

Learning from participatory research

Everyone who worked on the air quality monitoring research agrees that building relationships and trust is key. That goes beyond just getting the work of the project done: “Those links with community are some of the only ways that we find the steadfastness to continue on, to continue working or fighting,” said Iwasaki. “How do you empower people who feel like, at every turn, there’s another factor of danger in their environment?” She notes that especially now, post-pandemic, communities can feel like the number of things to be concerned about or frightened of are overwhelming. It’s important to provide options and opportunities for residents to choose what they want to do to protect their health.

Pfotenhauer said the experience changed his perspective on practicing science: “The relationship-building aspect of science is paramount – you learn so much more through that participatory research,” he said. “Now as a scientist, I’m more grounded in thinking about what’s important to the public – what do they know, what do they want to know?”

As Collier-Oxandale wrote in her Thriving Earth Exchange blog, participating in the pilot project showed her that her skills as a scientist were valuable outside of academics: “We, as scientists, have more skills and broader knowledge than we realize (e.g., reviewing/translating scientific literature and reports, or grant writing and project planning) and it is possible to use these skills and resources to support community-based work in a meaningful way,” she said. “Think about being flexible, adaptable, and willing to go into new areas.”

The project also brought home how effective participatory research is at building trust. “The group of older people who were leading this, they were leaders and protectors in the community. They said, ‘this is what we are doing,’ and they did a lot of the recruitment,” said Ware.

What’s next for radon mitigation in Denver? With each of the three studies, more and more residents learned about, tested for and started seeking remediation of radon in their homes. The city of Denver has also become more proactive about radon, with the city’s mayor calling for residents to be aware of its risks and expanding radon remediation programs for residents with low incomes. Thanks in part to the project, the Denver Urban Renewal Authority now offers no-cost loans in Denver to remediate radon: Before beginning sampling, Ware reached out to the organization about adding radon to the list of home repairs they cover, enabling a pathway for residents with low incomes to protect their health.

But the project team emphasizes the importance of understanding radon as an environmental hazard in the context of the other concerns facing communities in Denver and across the country – including outdoor air quality, pollution and urban heat. As Collier-Oxandale noted, “participating in community-based science has also helped me to see my work in a larger context, as often your community partner is working on or at least thinking about a variety of issues affecting their community, beyond your project and area of expertise.”

TNH2H’s indoor air quality monitoring projects were successful for many reasons. They were guided by community voice; actively involved residents and responded to their questions; and provided open access to the resulting data and potential solutions. But above all, it is the deep trust between TNH2H, its participants, and their neighborhoods that sets their work apart – and leaves the door open for future community-directed research that can make a difference in residents’ lives.