Lev Horodyskyj is an astrobiologist and educational innovator formerly with the Arizona State University’s Center for Education Through eXploration. He currently freelances and is developing his own cross-cultural science education projects.

By Lev Horodyskyj

I realized that I had stopped talking and that I was listening instead. I had no choice because I couldn’t understand what was being said and had to listen instead to real-time interpreters who were translating the consultant to mayor of Las Terrenas, Nora Lis Cavuto, Spanish into words I could understand. She described the community with which she had fallen in love, Las Terrenas on the northern coast of the Dominican Republic. An idyllic town of fishermen and vacationers, gorgeous coastlines with islands and reefs, historic local houses, and chic hotels. But there was trouble as well. The river that ran through downtown was polluted with garbage and solid waste, which emptied onto the reefs. Already the reef closest to the coast was dead and the one beyond was dying. The loss of the reefs had resulted in bigger and stronger waves, especially during hurricanes intensified by climate change, which was leading to more rapid erosion of the coast. Loss of coastline meant loss of roads and infrastructure and was soon to threaten the hotels that brought in the rich customers.

I had decided to attend the Thriving Earth Exchange events at this past December’s American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting because I was looking to build stronger connections between the work I do and the communities on whose behalf I ostensibly work. Because I work on improving online science education, I often feel disconnected from the people I teach. We are perpetually separated by many screens. Over the years, I felt that I had lost touch with what drives people to seek a science education. Sure, I could see what they posted on a discussion board or analyze their extensive data trails through my courses. But at some point, these remote data need to be “ground truthed.” Am I interpreting their data trails correctly? Do repeated attempts represent struggle and frustration or genuine curiosity? And why do I see differences among different groups of people? Why do some repeat the same task until it’s perfected while others walk away after a single failure? What, in other words, do they expect and want to get out of science?

I had decided to attend the Thriving Earth Exchange events at this past December’s American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting because I was looking to build stronger connections between the work I do and the communities on whose behalf I ostensibly work. Because I work on improving online science education, I often feel disconnected from the people I teach. We are perpetually separated by many screens. Over the years, I felt that I had lost touch with what drives people to seek a science education. Sure, I could see what they posted on a discussion board or analyze their extensive data trails through my courses. But at some point, these remote data need to be “ground truthed.” Am I interpreting their data trails correctly? Do repeated attempts represent struggle and frustration or genuine curiosity? And why do I see differences among different groups of people? Why do some repeat the same task until it’s perfected while others walk away after a single failure? What, in other words, do they expect and want to get out of science?

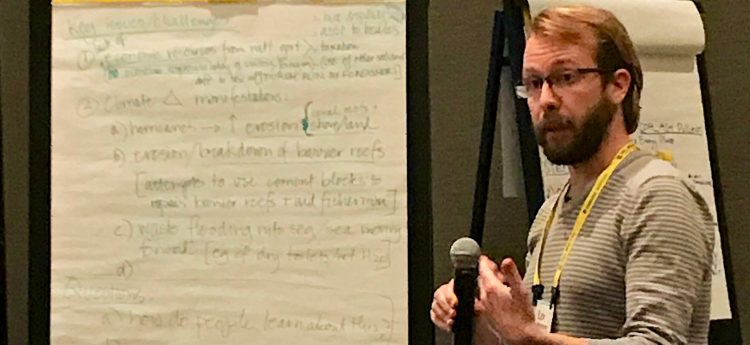

The Community Science 101 Thriving Earth Exchange event was a great starting point for learning how to ask better, more probing questions to understand what communities want out of science. Too often as a scientist, I listen just long enough to try to discern the problem and then render a solution. The Community Science 101 event, however, proposed a different approach, one centered on “active listening.” In this approach, asking deep, probing questions lets the community members, rather than the scientist, drive the conversation. After all, the scientist is there to be a reference to help a community address an unmet need, not an actual decision maker. We were able to role-play as scientists and community leaders and despite getting a primer on how to do better active listening, I noticed that I still tended to jump to solutions before fully understanding the community. This would require more practice.

The Community Science 101 Thriving Earth Exchange event was a great starting point for learning how to ask better, more probing questions to understand what communities want out of science. Too often as a scientist, I listen just long enough to try to discern the problem and then render a solution. The Community Science 101 event, however, proposed a different approach, one centered on “active listening.” In this approach, asking deep, probing questions lets the community members, rather than the scientist, drive the conversation. After all, the scientist is there to be a reference to help a community address an unmet need, not an actual decision maker. We were able to role-play as scientists and community leaders and despite getting a primer on how to do better active listening, I noticed that I still tended to jump to solutions before fully understanding the community. This would require more practice.

A better test came the next day at the Thriving Earth Exchange Project Launch Workshop. As I scanned the room for groups to join, I was drawn to one that seemed challenging, a table that required interpreters because of a language barrier. It was a group that was different from all the others and that intrigued me. Remembering what I had thought I learned the previous day yet failed to apply, I tried to do better this time. Surprisingly, I found that the language barrier helped. Because the interpreters could only translate so much chatter at once, we all slowed down the conversation so that we did not talk over each other and so that everyone could be heard and, more importantly, understood.

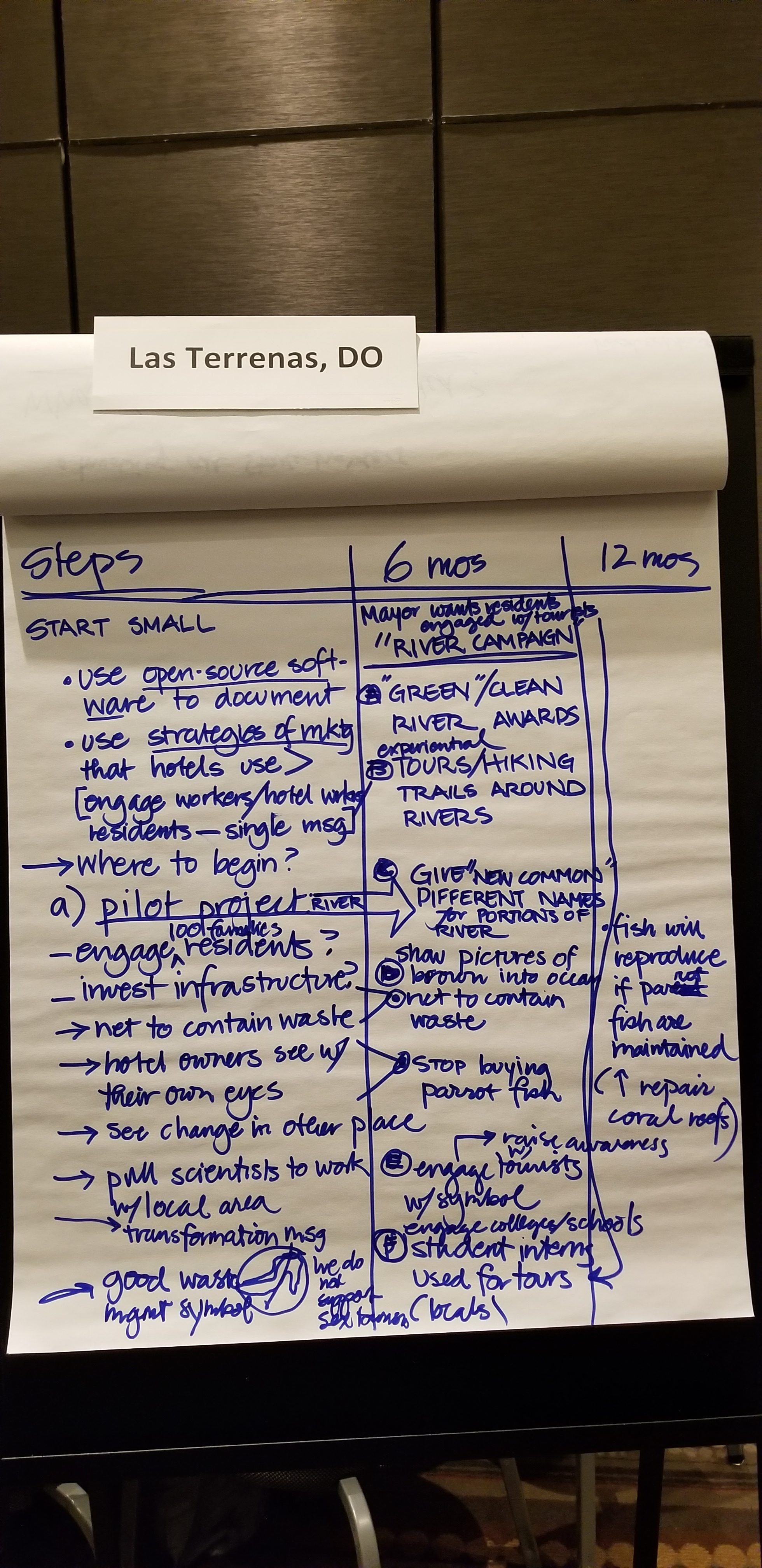

By the end of the workshop, we hadn’t made as much progress as teams who didn’t have to contend with a language barrier. However, the conversation felt deeply respectful and involving. We came away with ideas for how we could get started. Because so many of the problems started at the river, it seemed reasonable to start with a community project centered on it, modeled after river rehabilitation approaches taken in cities around the world. Rather than just a simple cleanup, we decided that a more sustainable approach would include transforming the river into a public space so that its maintenance wasn’t a chore but a point of community pride. What this community wanted out of science was explanations and how they could lead to solutions generated by the community itself, not just more data. And they wanted a broader conversation within their community—one that crossed not just the language barriers with which we had successfully contended in the workshop, but the broader cultural one between those who live in Las Terrenas and those who simply visit.