Apply now to join our next cohort of Community Science Fellows and Community Leads!

Photo courtesy of the Town of Colebrook

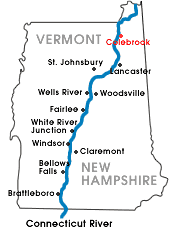

The community of Colebrook, New Hampshire is a small, rural community. It is located in northern New Hampshire, close to the Canadian border. The town’s closed municipal landfill has 1-4 dioxane leachate entering its groundwater systems. To date, 1,4-dioxane levels exceed New Hampshire’s Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQS). The sub-surface groundwater contaminant plume has migrated from the town’s property boundary and has been detected on an abutting property. The plume has resulted in groundwater degradation near Lime Pond, a surface water body located just across the municipal boundary in Columbia, New Hampshire. To prevent contamination of the pond, the Town installed a groundwater extraction system to manage contaminant plume migration. Water extracted from the subsurface is subsequently transported to the town’s wastewater treatment facility where it is treated with raw waste and discharged into the Connecticut River. The wastewater is treated with a system of aerators, mixers, and ultraviolet (UV) light. Colebrook would like to review the current state of the landfill site and investigate whether any emerging treatment systems offer a long-term, sustainable and cost-effective solution. The town hopes to treat 1-4 dioxane in situ (in the ground). Ultimately, this project seeks to deliver a comprehensive report describing the source character of 1,4-dioxane contamination a review of emerging treatment alternatives.

The Colebrook, NH project launched at the December 2016 Thriving Earth Exchange Project Launch Workshop in San Francisco, CA. There then Colebrook town manager, Becky Merrow, attended to describe the 1-4 dioxane situation in her town to a group of AGU scientists. Dave Ellerbroek, one of the scientists at the Colebrook table at the Project Launch Workshop, ended up being the scientific partner selected for this project.

From January 2017, Ellerbroek worked with Merrow and a town consultant to work with the community to determine the nature and extent of contaminants and remedial approaches or treatment options. As a first step, the Ellerbroek agreed to build upon different treatment options listed by Merrow by developing a site conceptual model. They used Ellerbroek’s Colorado School of Mines’Groundwater Contaminant Transport masters students to have students illustrate what is known and not known of the hydrogeology of Colebrook site. The team would then use the site conceptual model as a decision-making tool/discussion format of what they propose to do with the site. Specifically, they will use this model to:

By June 2017, Colebrook received $5000 grant to do sampling and analyses. At that point they had a draft menu of treatment technologies.

By November 2017, the team had a call for interns to to sampling and analyses with the consultant in Colebrook in Spring 2018. Brad Geismar was selected to undertake this task and produce a final report.

In April of 2018, Brad Geismar met with a variety of members of the Colebrook community and, with their help, assembled a comprehensive report describing the history and evolution of the municipal landfill remediation site. Following conversations with professionals in the environmental remediation field, Brad Geismar also utilized a variety of electronic resources and conversations with product representatives to conduct a survey of emerging remediation technologies and then suggest which emerging technologies might be most applicable to the Colebrook context.

To complete the report, Brad Geismar accessed to municipal and state records describing the qualitative and quantitative evolution of the landfill remediation site as well as a comprehensive explanation of operations already conducted at the site. Brad acquired this information by meeting with community members, going through physical town records, and reviewing electronic records maintained by the state of New Hampshire.

The entire project team conducted bi-weekly remote check-ins. Brad Geismar, the TEX intern, also had an opportunity to spend two weeks working in the Colebrook Community.

As a result of the project, the team presented the Town manager of Colebrook with a report to share with the Board of Selectmen summarizing the landfill site situation and discussing a variety of future actions the town might take. The town was encouraged to use the report to help identify what resources are most helpful for keeping the various community members directly responsible handling the management of the landfill site up to date on the condition of the site and informed regarding what technologies offer appropriate remediation alternatives.

Other towns facing 1,4-dioxane remediation challenges similar to those presented by the Colebrook municipal landfill might look at the Colebrook report as an updated source of information discussing what factors should be considered when treating 1,4-dioxane, what technologies are available, and what factors help determine which methods allow for the most cost-effective treatment of 1,4-dioxane.

Some things that contributed to the team’s success include:

Some things that contributed to the team’s success include:

If they were able to do this project again, they would:

For those interested in pursuing a similar community science project, the team recommends recognizing that community members often have in-depth, albeit potentially fragmented, knowledge bases about the problem that can span years. Build relationships with those community members so you can access information quickly.

*The photo above shows Brad Geismar collecting a water sample from monitoring well 18B so that the Town of Colebrook can create an updated model of contaminant plume migration and 1,4-dioxane contaminant levels. While working with the town of Colebrook, Brad assembled the results of similar surveys to create a comprehensive report detailing the history and evolution of the landfill site, a survey of emergent technologies that might be used to help remediate the site, and suggestions for actions the town might take moving forward. During his time in Colebrook, Brad had an opportunity to see the current remediation system operating at the site and to visit and sample monitoring wells located around the site.

The community of Colebrook, New Hampshire is a small, poor, rural community. It is a remote village located at the northern tip of New Hampshire. Colebrook has the highest unemployment in the State. Weather and climate is a factor. It gets cold in Colebrook. In January, temperatures will reach -40 degrees Celsius.

The community of Colebrook, New Hampshire is a small, poor, rural community. It is a remote village located at the northern tip of New Hampshire. Colebrook has the highest unemployment in the State. Weather and climate is a factor. It gets cold in Colebrook. In January, temperatures will reach -40 degrees Celsius.

The town’s closed municipal landfill has 1-4 Dioxane in the groundwater. The levels present exceed Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQS). The polluted groundwater has left the property boundary and is present on land of an abutter.

The plume has resulted in groundwater degradation in the vicinity of Lime Pond located just across the municipal boundary in Columbia, New Hampshire. This waterbody is an extraordinary example of a marl pond. Its bottom holds 6 feet of nearly pure, white marl, made up largely of shells of freshwater mollusks known as cyclas and planorbis that still live in the pond, usually under loose stones. The bedrock surrounding the pond is an impure, gray and blue limestone from which the calcium that defines the pond has leached over the past 10,000 years.

To protect the pond, the Town was required to install a groundwater extraction system to collect groundwater. This groundwater is then trucked across town to the municipal wastewater treatment system. The Town then treats the groundwater as it does raw waste and discharges it into the Connecticut River. The wastewater is treated with a system of aerators, SolarBees (mixers) and ultraviolet (UV) light. Locally, this system is referred to as a “pump and dump” method.

Thus, the community has a groundwater dioxane problem associated with the landfill. Colebrook would like to know how they might determine a long-term, sustainable and cost-effective remedy. The goal is to remediate the 1-4 Dioxane in situ (in place).

Becky and Dave will work together to provide a menu of remedies and costs for a “walk away” solution. The team anticipates that this project will take approximately 12 months. The primary deliverable(s) for this project will be a source characterization report and treatability studies.

Becky Merrow, Esq. earned her Bachelor of Science Degree in Paralegal Studies from Woodbury College (now Champlain College) located in Burlington, Vermont. She has been working in public administration since the 1990’s. She has been the Town Manager of Colebrook New Hampshire since 2012.

Vermont has a unique program that allows individuals with a bachelor degree to “Clerk” for the bar. Commonly referred to as “reading the law,” the program is an apprenticeship platform which takes 4 years to complete. Upon successful completion, she was deemed qualified to sit for the Vermont Bar Examination and was sworn in as a member of the Vermont Bar Association in June of 2009. This is the same manner that President Abraham Lincoln and Vermont Supreme Court Justice Marilyn Skoglund were allowed to practice law.

Becky enjoys kayaking and travel and is passionate about the community she serves. She is the grandmother of 5 year old Maggie Lorraine Newton.

Dr. David Ellerbroek serves as the Denver Area Manager for AECOM and oversee operations related to transportation, water, environment and urban facilities. He is passionate about natural resource development and have spent significant portion of my career working on methods to mitigate environmental impacts and protect water resources during natural resource development. My career has included international work for O&G and mining companies (Australia, Argentina, Peru and Chile), several large remediation projects including serving as Client Service for the El Paso Corporation remediation program and developing water management solutions for unconventional Oil and Gas development.

In April 2018, Bradley Geismar will be spending two weeks in Colebrook, NH to help the town investigate groundwater management solutions for its municipal landfill. Hailing from Minot, ME, Brad grew up hiking, canoeing and backpacking in the woods of Maine and New Hampshire. A woodsman at heart, Brad balances two passions – his enthusiasm for the outdoors and his desire to help communities solve complex environmental management challenges. As an undergraduate at Dartmouth College, Brad studied Earth Sciences and led interdisciplinary trips for Dartmouth’s Outing Club. In the classroom, Brad honed his technical environmental management skills and focused on studying interactions between surface and sub-surface systems. Out of the classroom, Brad used his experience as an outdoorsman to help build community while leading trips such as Dartmouth’s freshman orientation white-water kayaking program in beautiful Errol, NH. Having graduated from Dartmouth College in Fall of 2017, Brad is excited to enter the field and use his knowledge to help community members collaboratively address environmental challenges. If you see him around town or trekking about the woods, be sure to stop and say hi!

Brad Geismar, 2018 TEX Community Science Fellow for Colebrook, N.H.

Located in northern New Hampshire close to the Canadian border, Colebrook, N.H. is a small town like many New England towns. Many of the town’s residents have ties to the community and its beautiful outdoor spaces that span generations.

Unlike other small New England towns, however, the Town of Colebrook is currently engaged in a decade-spanning effort to remediate 1,4-dioxane contamination of its municipal landfill. The project has already cost the town hundreds of thousands of dollars and over the years Colebrook has hired several environmental remediation companies to help assess and address the issue.

The Town of Colebrook partnered with TEX to bring volunteer scientists to help re-assess the current state of the landfill remediation project and evaluate whether any new remediation technologies might be viable at the landfill site. TEX Community Science Fellow Bradley Geismar reflects on the community resilience and fragility he encountered while engaging in collaborative community science to support this project:

Months before I arrived in Colebrook, N.H. I had a conversation that caused me to pause and reflect upon the role a scientist plays when visiting a community to help address a technical problem. The conversation occurred during a phone call I had had with David Ellerbroek, an established professional scientist consulting with Colebrook through the TEX program, and Becky Merrow, Colebrook’s Town Manager.

David and I began to focus on the particular challenge of finding a cost-effective, efficient and easy-to-operate system for remediating the 1,4-dioxane contaminated groundwater around the landfill. 1,4-Dioxane groundwater remediation is performed by ex-situ (above surface) or in-situ (below surface) systems that remove or neutralize any 1,4-dioxane within the contaminated water.

Just as David and I were beginning to animatedly discuss the promise that a newer technique called in-situ bioremediation could hold for sites like the Colebrook landfill, Becky said something that brought David and I back to Earth. “I’m not the scientist here,” Becky began, “but how would contaminant-eating bacteria handle a New Hampshire winter?” After a moment’s pause and a wry chuckle from David, both David and I said that the bacteria probably wouldn’t find a New Hampshire winter very hospitable. We decided that, for the time being at least, we could probably take in-situ bioremediation off the list as a remediation option.

Finding my role

That early conversation framed the rest of my time with the project, presaging the fact that one of the most useful things I could do for the folks of Colebrook would be to act as an information assembler and filter.

Even though I held specialized expertise as a scientist, I was humbled by the knowledge base, familiarity with, and connection to the landfill site the members of the Colebrook community had accumulated over nearly a decade and a half of managing the site and generations of living in the region. I had a chance to meet with a wide range of community members. I met the town manager, members of the Board of Selectmen and many of the incredible folks who keep the town running on a day to day basis. I met the operator of the pump-and-treat remediation system currently operating at the landfill site, and the head of the Colebrook’s wastewater treatment facility. I also met a representative from the environmental remediation firm currently helping the town monitor and manage the landfill site, and a group of high school students who were learning about water resources in their environmental science class.

With each meeting, I saw how various Colebrook residents played key roles in both managing current remediation operations and planning the long-term future of the remediation site. Many of these folks understood the landfill remediation operations to a degree that would have taken me quite a lot of time to assemble on my own.

My major contribution to the project was to write a report that summarized the evolution of the landfill site, outlined emerging remediation technologies and evaluated which emerging remediation technologies might be appropriate for the site. I relied upon support from many community members to help guide me toward the information for this report, yet during my time in Colebrook, many people asked me questions and commented on how my background as a scientist must leave me well-equipped to help them choose the most effective solution to the landfill problem. Such comments, along with my experiences meeting with various community members in town, helped me realize one of the key challenges faced by small communities trying to address long-term technical challenges: The task of creating and preserving the institutional knowledge required to address a problem that spans years, and even decades.

Preserving knowledge

Even though the knowledge of the remediation history and process at the landfill site collectively exists within the town and many people have active access to it, I came to see that in the community context such information is rarely comprehensively held by one person and that it can easily become increasingly fractured over time. The town manager might understand that the landfill needs to be remediated and that clean-up operations will cost the taxpayers. The Board of Selectmen might know how funding for that clean-up might get allocated over time. The remediation system operator might understand the technical details of how the system operates. The wastewater treatment facility operator might know how much water from the remediation system gets brought to the facility over time.

Each of these people represents a node of information and understanding. When each node is in communication with the other nodes, comprehensive knowledge can be preserved and readily accessed. However, when these nodes are unable to consistently remain in contact with one another, the comprehensive character of the information each node contains degrades until a holistic view of the situation is lost.

The challenge of resilience

By working collaboratively with members of the Colebrook community, I learned how, even without a team of scientists, communities can build resilience that allows them to handle remediation challenges. In many ways, Colebrook represents a community in which the community members that represent various nodes of information communicate well and work together effectively. This ability to communicate and work together has left the town with an institutional memory of the landfill site that allows the community to remain resilient over time.

Nevertheless, even Colebrook is far from immune to the fragility that can be caused by interruptions in communication between different members in the community. Many of the people in town who directly handle the landfill site remediation efforts are in public service positions that have the potential to change on the year rather than decade scale. Since the town faces a remediation process that has already spanned a decade and a half and is likely to persist for years to come, Colebrook will certainly have to continue to work to maintain its resilient character moving forward.

Becky Merrow, Esq. earned her Bachelor of Science Degree in Paralegal Studies from Woodbury College (now Champlain College) located in Burlington, Vermont. She has been working in public administration since the 1990’s. She has been the Town Manager of Colebrook New Hampshire since 2012.

Vermont has a unique program that allows individuals with a bachelor degree to “Clerk” for the bar. Commonly referred to as “reading the law,” the program is an apprenticeship platform which takes 4 years to complete. Upon successful completion, she was deemed qualified to sit for the Vermont Bar Examination and was sworn in as a member of the Vermont Bar Association in June of 2009. This is the same manner that President Abraham Lincoln and Vermont Supreme Court Justice Marilyn Skoglund were allowed to practice law.

Becky enjoys kayaking and travel and is passionate about the community she serves. She is the grandmother of 5 year old Maggie Lorraine Newton.

Dr. David Ellerbroek serves as the Denver Area Manager for AECOM and oversee operations related to transportation, water, environment and urban facilities. He is passionate about natural resource development and have spent significant portion of my career working on methods to mitigate environmental impacts and protect water resources during natural resource development. My career has included international work for O&G and mining companies (Australia, Argentina, Peru and Chile), several large remediation projects including serving as Client Service for the El Paso Corporation remediation program and developing water management solutions for unconventional Oil and Gas development.

2018 Thriving Earth Exchange Community Science Fellow Remediation Report Download

(c) 2024 Thriving Earth Exchange