Apply now to join our next cohort of Community Science Fellows and Community Leads!

Local sources of pollution in the Conodoguinet Creek Watershed impact surface and groundwater. These contaminants have an adverse effect on the quality of municipal and well-drinking water sources, locally caught fish and other aquatic life, wildlife, biodiversity, and recreational safety (fishing, swimming, and boating). This project aims to collect and analyze a baseline of information from existing data, maps, and fieldwork to assess sources of contamination and their possible impacts. Community education, engagement, and action will be emphasized throughout the project. A final report will include recommendations for immediate actions and suggestions for further monitoring, testing, and remediation.

Move Past Plastic has brought together a grassroots group of organizations, including local government, academics, scientists, experts, and concerned citizens living in and around the Conodoguinet Creek watershed. The Conodoguinet Creek snakes for 104.5 miles from the Kittatinny Ridge, down the Cumberland Valley, and into the Susquehanna River near Harrisburg. It cuts across Franklin and Cumberland counties East to West and touches Dauphin County. This 524-square-mile watershed is home to 40 municipalities and predominantly resides in Cumberland County, the fastest-growing county in Pennsylvania. The area also includes Dickinson College, Shippensburg University, Army War College, and the Naval Support Activity in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania. The watershed also has two world-renowned high-quality limestone trout fishing streams: Yellow Breeches and LeTort Creek.

Before 2000, the area was primarily rural and agricultural. Since 2000, significant farmland has been replaced with suburban sprawl, including housing, warehouses, and big box stores. Challenges to the creek include intense stormwater runoff carrying pollutants and sediment. In addition to nonpoint source pollution from developed impervious surfaces, there is potential point source pollution from several manufacturing facilities that use per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

The community would like to establish a baseline of contamination—including Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS), Heavy Metals, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs), Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs), Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) and other contaminants such as pharmaceuticals and personal care products—from existing data, maps, and fieldwork to assess actual and potential point source chemical contamination and determine current and future impacts.

A report will provide an analysis and a conclusion recommending further monitoring, testing, and remediation. Known and potential point and non-point source contamination with and without current toxicity data will be identified. It will include abiotic and biotic data, charts, graphs, and maps. Known data will include chemical and biotic type, testing dates, locations, and amounts.

The recommendations will also include wastewater discharge and treatment by both industry and municipality, drinking water treatment by the municipality and third-party providers, restrictions on landfill leachate land application of biosolids if contaminated with PFAS, remediation by military base if contaminated, and measures that homeowners could take like installing filters on faucets used for drinking and cooking.

These recommendations will be shared with the municipalities in the Conodoguinet watershed’s local and county government, NGOs, colleges/universities, scientists, businesses, farmers, and residents. The information will help drive further education, research, science, and policies to minimize and clean up contamination. The recommendations will also be used to apply for grants to further educate, research, and prevent and remediate contaminated areas to improve the watershed’s health and the local community’s health. Community education, engagement, and action will be emphasized throughout the project.

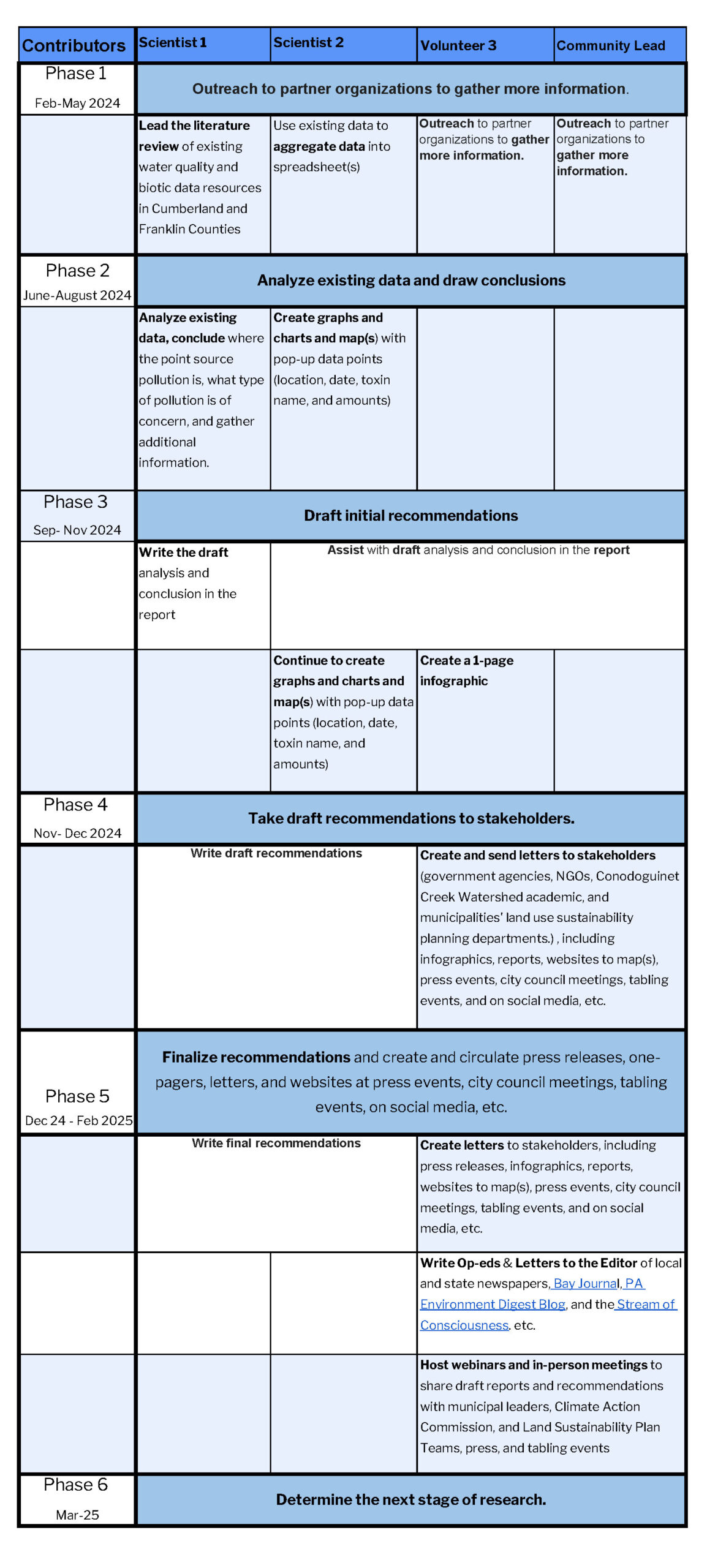

February – March 2024: Recruit Community Scientists and revise scope if needed.

March – June 2024: Initial literature review. Outreach to partner organizations to gather more information.

June – September 2024: Analyze existing data, draw conclusions on where point source pollution is, what type of pollution of concern, and gather additional information.

October – December 2024: Draft initial recommendations.

December 2024 – January 2025: Take draft recommendations to stakeholders.

February – March 2025: Finalize recommendations and create and circulate press releases, one-pagers, letters, and websites at press events, city council meetings, tabling events, on social media, etc.

April 2025: Determine the next stage of research.

View Timelines and Milestones Chart Here

Tamela Trussell. Tamela is the founder of Move Past Plastic (MPP) and TLC Education, a Climate Reality Leader, a Master Watershed Steward, a committee member of the Carlisle Climate Action Commission, and a board member of the Conodoguinet Creek Watershed Association.

Karen Green co-founded Pidcock Creek Watershed Association in the Delaware River watershed and is a current member of Conodoguinet Creek Watershed Association and Move Past Plastic; she and her husband are also Hellbender contributors to the Lower Susquehanna Riverkeeper.

Shashank Anand is a postdoctoral research scholar in the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering at Texas A&M University. His primary focus involves enhancing the modeling approach for organic carbon dynamics under various land management practices and shifting climatic conditions. Shashank earned his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 2023.

Chiara Smorada is a graduate student in Princeton University’s Civil and Environmental Engineering Department. Her current research focuses on the biological degradation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in soil and river water. She studies microbial community shifts in PFAS-impacted sediment and investigates enzymes that may play a role in PFAS defluorination. She looks forward to sharing her knowledge about PFAS to empower others to engage in environmental stewardship.

Marissa Kulkarni is a Geospatial Specialist located in Santa Clara, California. She has deep experience with geospatial analysis, including remote sensing, spatial statistics, cartography, and ArcGIS software. Currently, she’s mapping utility-scale solar, wind, battery storage, and hydrogen energy facilities at RWE Clean Energy. As a Pennsylvania native and passionate environmentalist, she looks forward to supporting healthy, plastic-free waterways across the Conodoguinet Creek watersheds.

Astrid Lozano-Acosta is a science educator interested in inquiry-based learning and hands-on STEAM activities, with experience developing bilingual didactic materials. She has also performed data analysis of aerosol and groundwater information and volunteered with grassroots environmental organizations by providing scientific summaries, maps, and infographics.”

(c) 2024 Thriving Earth Exchange