How a researcher let the community be his guide while studying the shifting sands of Alaska’s North Slope

by Kathleen Pierce

Alaska’s North Slope faces some of the worst coastal erosion in North America. There, the ocean is eating away at the shoreline at the alarming rate of 4.6 feet per year on average and upwards of 60 feet per year in some locations. This severe erosion puts local infrastructure, homes and cultural assets at risk and is forcing retreat strategies in some coastal communities.

Michael Brady, a doctoral candidate in geography at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, found himself drawn to the region after conducting research on sea-level rise in New Jersey, doing coursework on Arctic geography and serving a stint in the U.S. Coast Guard. In an ongoing project in the North Slope, Brady is partnering with local stakeholders to help mitigate climate-related coastal hazards through a unique collaborative mapping approach that puts the community’s needs first and foremost.

A shift in the way science is done

Ancient dwelling mounds (foreground) and modern homes alike are threatened by rising sea levels along Alaska’s North Slope. Image courtesy of Michael Brady/Rutgers.

Rather than venturing alone to the North Slope, assessing erosion trends, and publishing his results in a scientific journal, Brady, a Human-Environment Geographer, chose to engage in a collaborative, mixed-methods research partnership with North Slope inhabitants. “The emphasis of this work is not on the environmental science,” said Brady. “It’s on the community engagement itself.”

His method is representative of a dramatic shift happening across many scientific fields. Local citizens, once viewed as non-experts whose involvement was best limited to simple data collection, are increasingly seen by scientists as stakeholders—and as partners—in the research process. Researchers, like Brady, are now inviting them to help design, participate in, and collaborate on projects that do not merely produce publishable results, but also affect how people live their daily lives. Brady believes these methods can enhance the usability of research and improve decision-making for local managers.

Serving the needs of the community

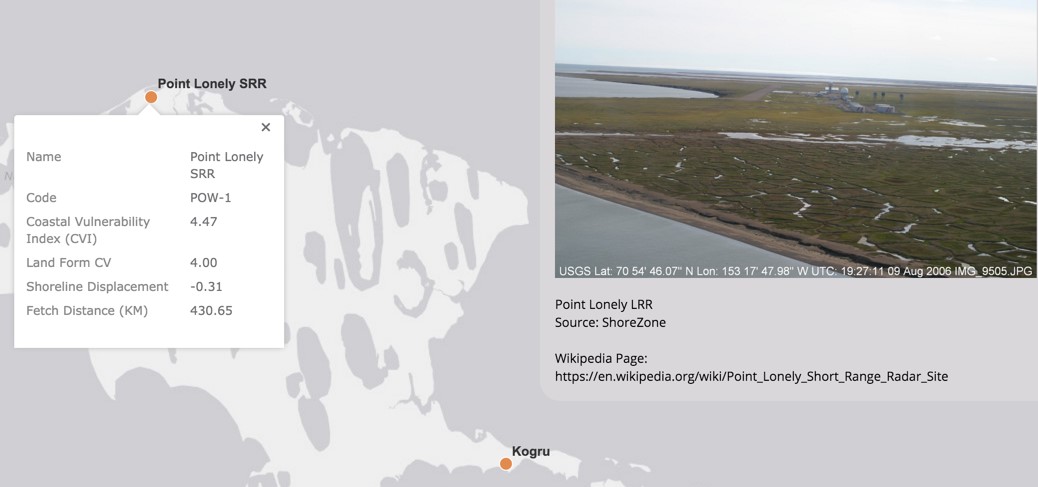

Detailed map of Point Lonely SSR, with a photo and erosion statistics, from Brady’s website.

When Brady first visited North Slope in 2013, his preliminary research set the stage for the personal, collaborative approach he wanted to take: He knocked on doors, hung out in public areas, and invited locals into conversations about the startling coastal erosion happening around them. Despite the “research fatigue” common in communities that find themselves in the scientific spotlight, once Brady described his research, people opened up. “Erosion seemed to ring a bell; they were interested in telling stories about that,” he said.

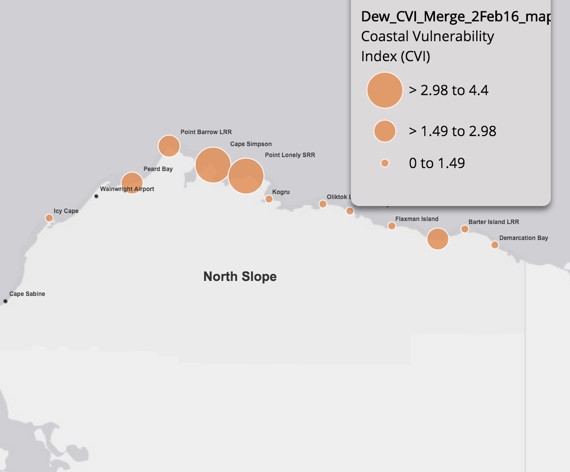

From these open, enthusiastic discussions, Brady was able to identify which areas the community most wanted to protect from coastal erosion. He created preliminary erosion maps by combining measurements of Arctic Ocean sea ice extent with the coastal vulnerability index of the U.S. Geological Survey and Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and then added the vulnerable areas locals were concerned about.

The preliminary maps, combining qualitative data gleaned from interviews and quantitative data taken from shoreline erosion factors and cartographic modeling, have come to serve as a conversation starter in the community. When the project is finished, Brady hopes they will not be merely maps but “boundary objects:” jumping-off points for focused community discussions around erosion risk, resource management, and mutual researcher-community understanding.

In addition to continuing to interview local inhabitants and borough officials, Brady also holds community workshops and conducts surveys to ensure the community’s interests are addressed. He is also developing a website with a suite of web-based tools to allow community members—or anyone in the world—to access and analyze the region’s coastal erosion risk.

A generalizable research approach

A map of North Slope, with orange dots to mark areas of coastal vulnerability, from Brady’s website.

Brady is passionate about citizen-engaged science and this collaborative approach to research. His research process can be adapted to any locality, and is in fact explicitly designed to do so.

“Researchers are often outsiders in the communities they study, but they needn’t remain that way,” said Brady. “Researchers will be most successful if they can go there and be flexible, and be very open to where the conversations might go.”

Brady aims to continue to work with North Slope stakeholders for years to come. By continuing these valuable conversations and providing stakeholders with more data and maps, he hopes his work can help them plan for whatever changes the future might bring.

This research is supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation awards 1523191, 0732973, and geospatial support from the Polar Geospatial Center under NSF 1043681 and by Applied Research in Environmental Sciences Non-profit. This U.S.G.S. report offers further information about North Slope erosion.

Kathleen Pierce is a contributing writer for Creative Science Writing and the Thriving Earth Exchange.